Working careers

The length of a person’s working career and their earnings during that career affect the level of pension security they will have. Efforts are being made to extend careers and increase employment rates to ensure the financial sustainability of the pension system as the population ages.

We study the stages, length, and earnings of working careers, as well as changes over time. In addition, we examine working alongside retirement and the differences between various demographic groups in the different phases of their working careers.

Development of working careers

Working careers have lengthened, particularly towards the end of the career span. Employment among those over 50 has increased more than employment earlier in the career. Women’s careers have extended more than men’s, although women’s careers are still shorter. Socioeconomic disparities remain significant in both the length of working careers and the ratio of employment to retirement.

Working careers have lengthened modestly and shifted to later ages

The Finnish Centre for Pensions measures actual working careers based on pension-insured employment, meaning work for which pension contributions have been paid. These are also referred to as gainful careers. It depicts an accumulated career over decades, from as far back as 1962. The Finnish Centre for Pensions measures the working career until the start of the old-age pension, so the gainful career does not include work done alongside receiving the old-age pension.

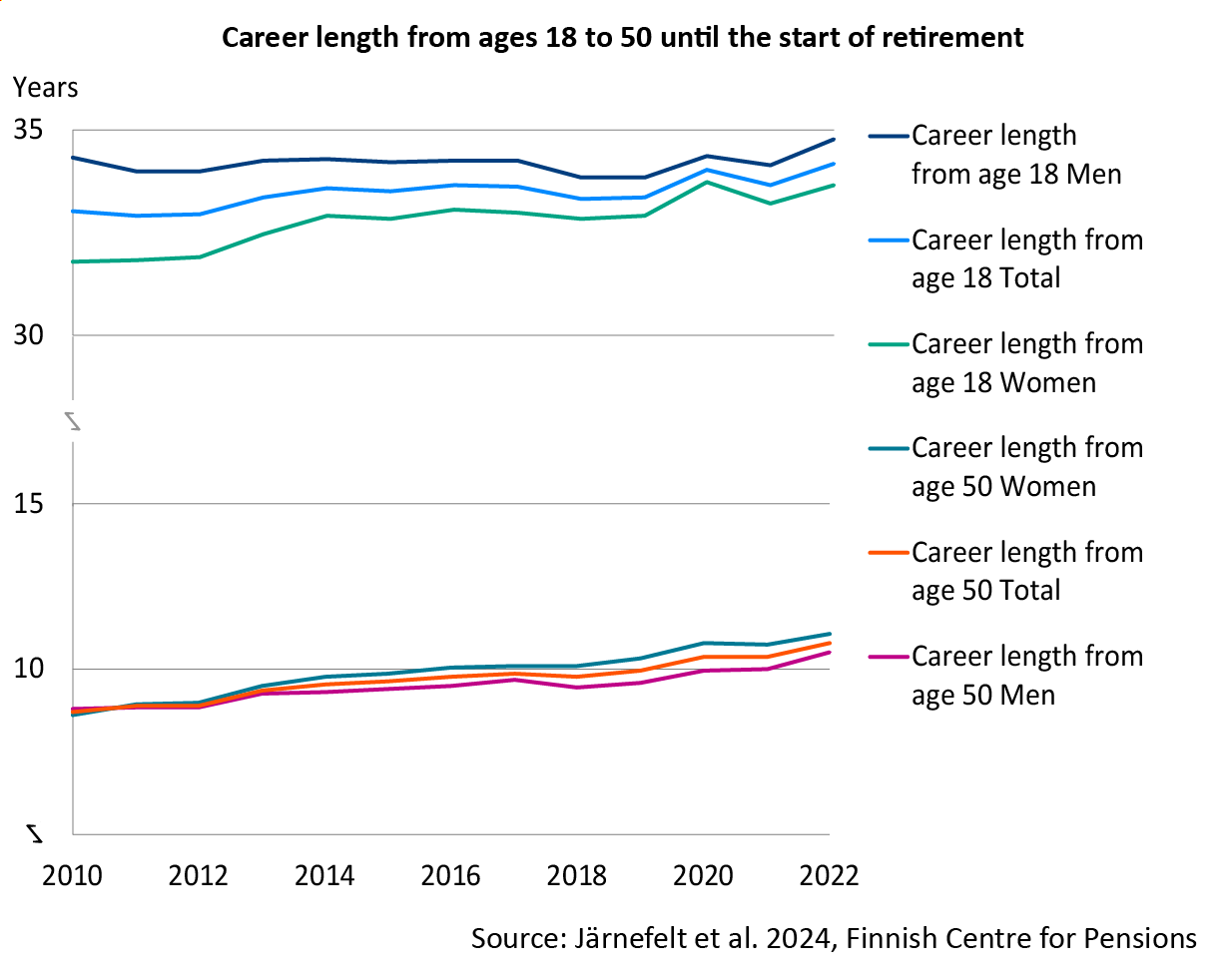

The gainful careers have been extended by an average of 1.2 years between 2010 and 2022, when the working career is calculated from the age of 18 until the start of the old-age pension. In 2022, the average length of working careers was 34.2 years. The median length of working careers was clearly longer than this, at 38.2 years. Half of the working careers were at least as long as the median at the start of the old-age pension.

The length of working careers for those over 50 has increased more than the overall length of working careers. Between 2010 and 2022, the length of working careers pursued after age 50 increased by 2.1 years on average. As working careers have lengthened, they have also shifted to later ages.

Women, those with lower education and those with disability have shorter working careers

Men accumulate longer gainful careers than women when working careers are calculated from the age of 18, but the gap has narrowed. Women’s working careers have extended significantly faster than men’s between the years 2010 and 2022. Especially for those over 50, women have accrued more career years compared to men. In 2011, women surpassed men in terms of the length of working career after age 50.

Working careers are clearly shorter if the old-age pension is preceded by disability pension. In 2022, against the background of a disability pension, the average career at the start of the old-age pension was 27.2 years. It is possible to work to a limited degree while receiving a disability pension.

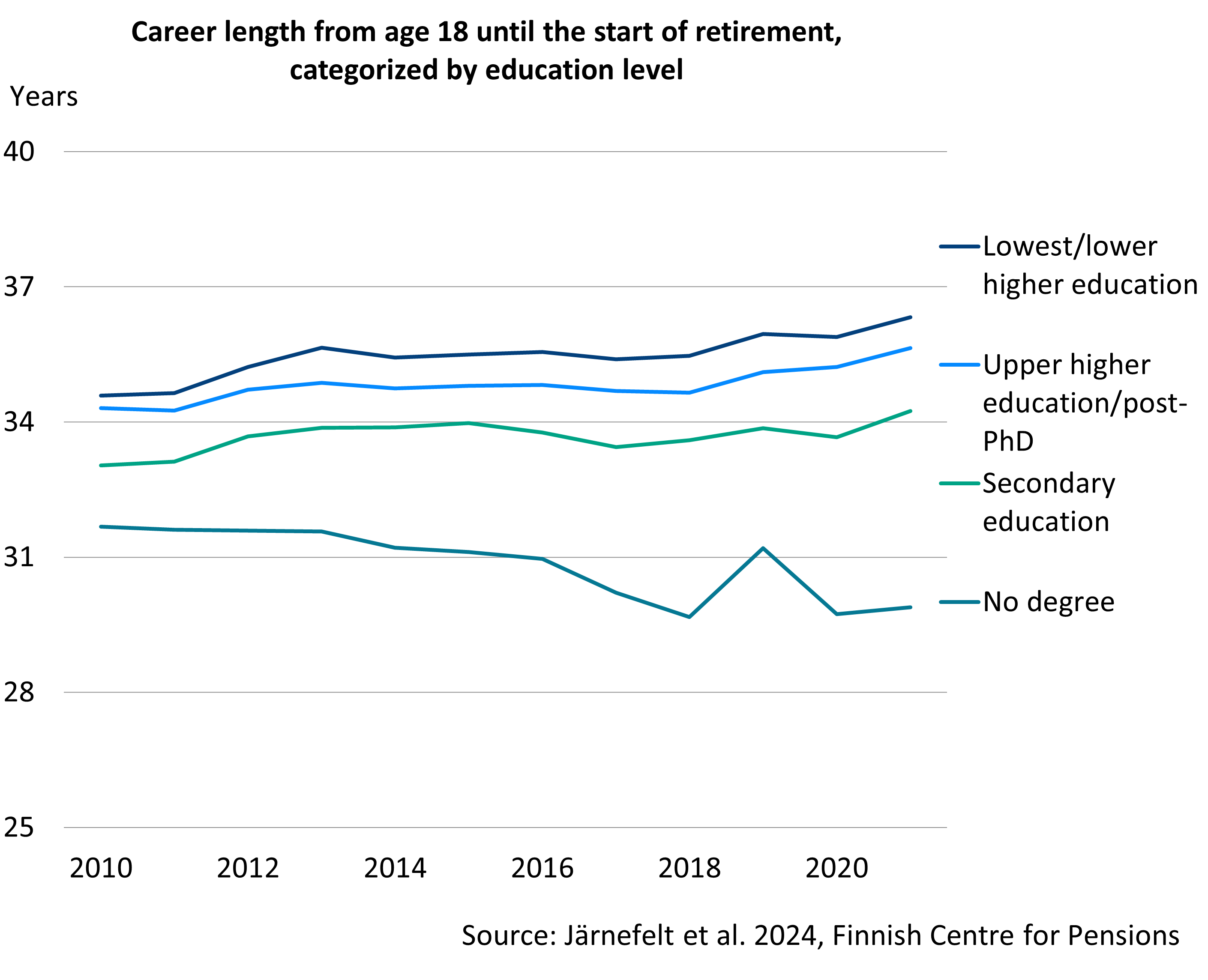

The length and development of gainful careers differ based on the level of education. For those with an upper secondary and lower tertiary degree, working careers are longer than for those with a higher tertiary or secondary education. However, working careers have been extended at all education levels. Conversely, those with only basic education have seen their working careers shorten. This is particularly true for men.

Publications:

As life expectancy increases, a slightly larger portion of it is spent in employment

The labour years ratio is one of the key indicators of the development of working careers, published annually by the Finnish Centre for Pensions. The labour years ratio is the ratio between the five-year average of the expected time in the labour force of an 18-year-old and the five-year average of the life expectancy of an 18-year-old. The higher the ratio is, the higher proportion of their expected remaining lifespan an 18-year-old will spend in the labour force. The labour years ratio is also calculated for 50- and 60-year-olds.

Life expectancy is increasing, and a growing proportion of a person’s expected lifespan is spent in employment. In 2024, an 18-year-old person is expected to be part of the labour force for 60 per cent of their remaining lifespan, up from 57 per cent in 2005.

Men’s labour years ratio is higher than women’s, but the gap between the sexes has narrowed over time. For those over 50, the labour years ratio has strengthened particularly significantly. A larger share of the expected time in the labour force is spent in employment, but employment trends have been weaker for younger age groups than for other age groups.

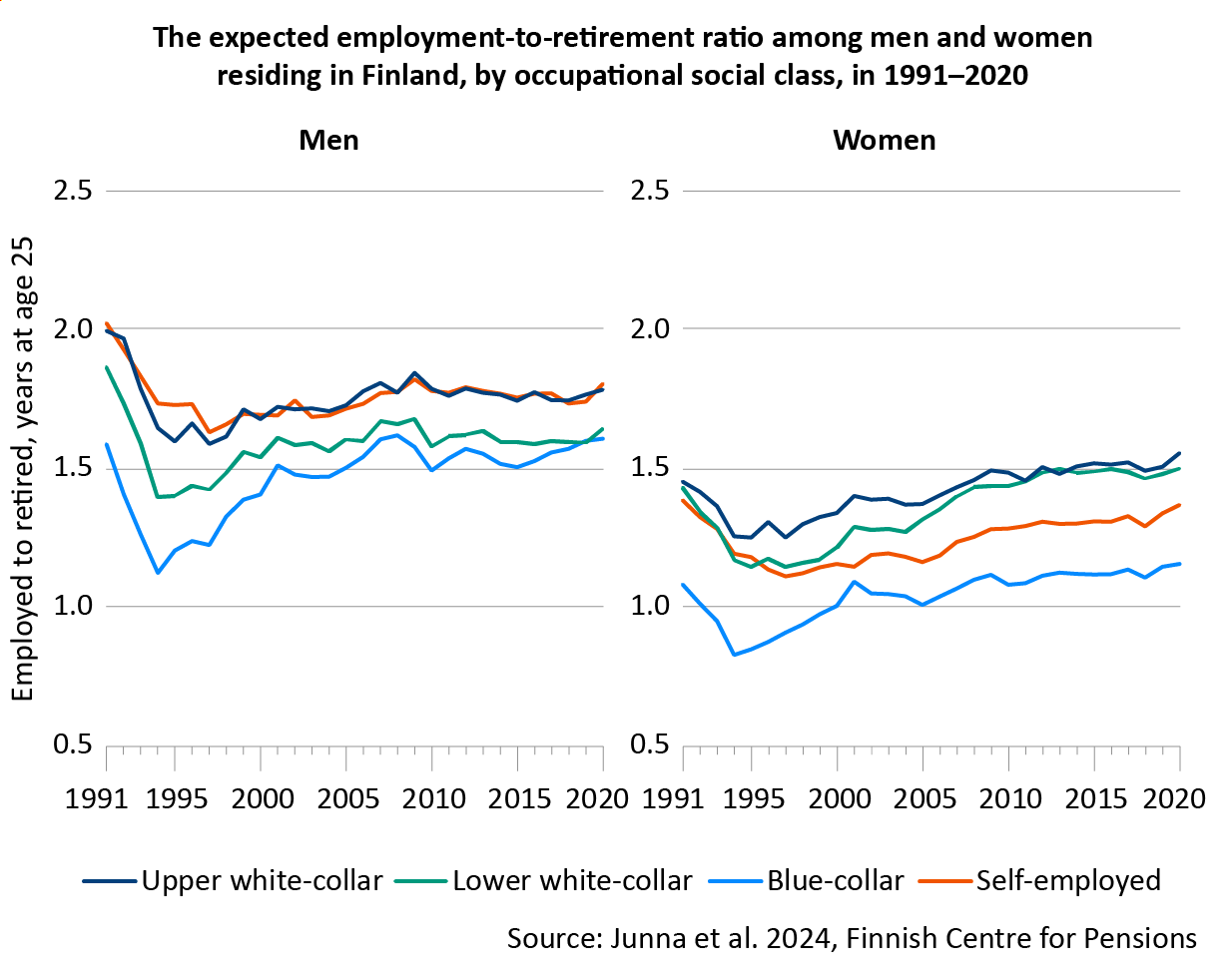

Distribution of expected lifespan divided into years in employment and retirement is clearly different according to socio-economic status

Among men, the gaps have narrowed slightly over the past few decades. In 2020, men in white-collar occupations were expected to work seven years and women nine years longer than their blue-collar counterparts. People in blue-collar occupations also experience longer periods of disability and less time in old-age retirement.

Life expectancy has risen in all groups, but the increase has been slower for those in lower socio-economic status groups. For men, the increase in life expectancy has been more evenly distributed between years spent in employment and in retirement, while for women, the increase in life expectancy has increased the number of years in employment.

Publications:

Read more on Etk.fi:

Extending working careers towards the end of the working life

As the retirement age has risen, working careers have extended at the end of working life. People are retiring later and with longer working careers. An increasing number of people are also continuing to work after they have retired on an old-age pension. Socio-economic and gender gaps have narrowed somewhat.

People are retiring with increasingly longer working careers

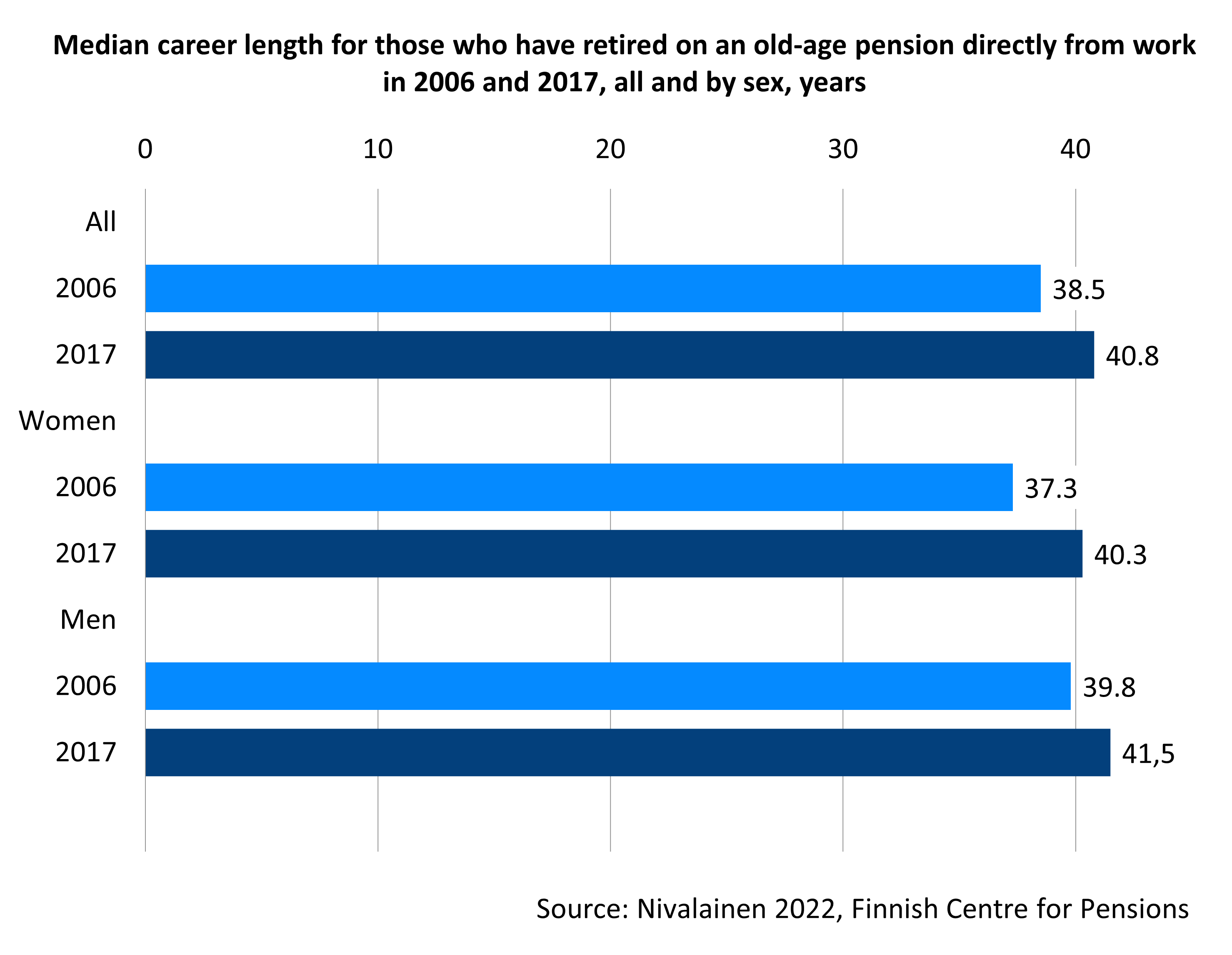

The median length of working careers has increased for those who have retired on an old-age pension directly from work. They had a median career length of almost 41 years in 2017, which is over two years longer than in 2006.

Women who move directly from work into retirement tend to have shorter working careers than men. However, women’s working careers have extended more rapidly than men’s. Between 2006 and 2017, women’s careers lengthened by three years, while men’s careers lengthened by just over one and a half years. The main reason for the increase in the length of women’s working careers is that they work longer towards the end of their careers.

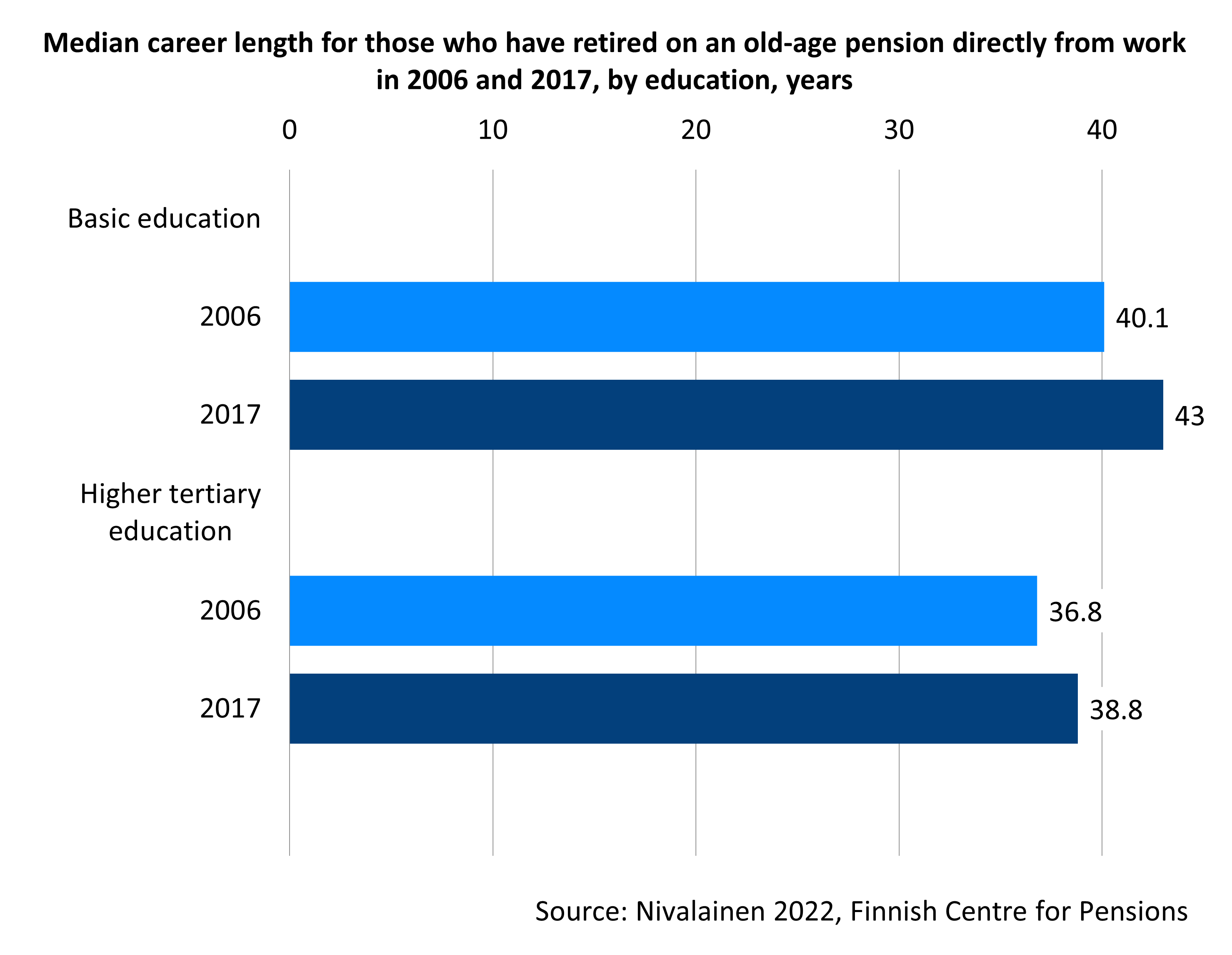

Those with a basic education who have retired from work have longer working careers than those with a higher tertiary education. The working careers have also extended more for those with a basic education. Workers in blue-collar occupations tend to have longer working careers than those in upper white-collar occupations, although the difference between these occupational groups is not as pronounced as the difference seen across educational groups. In different occupational groups, working careers have extended at about the same pace.

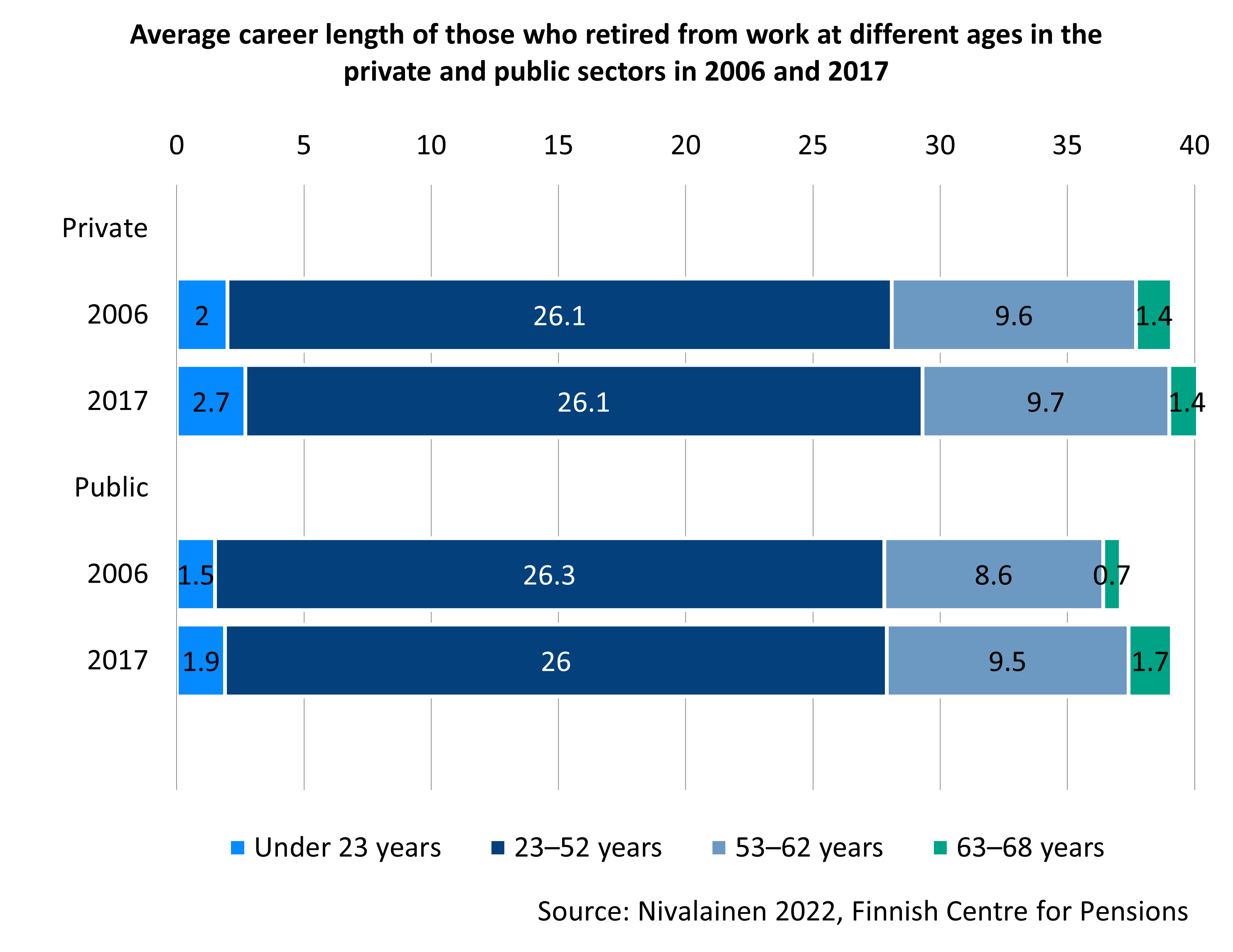

The gap in working career lengths between the private and public sectors has narrowed

In the private sector, the working careers for those who have retired on an old-age pension from work are longer than in the public sector, but the gap has narrowed. This is largely due to the average retirement age in the public sector rising significantly between 2006 and 2017, whereas there was no increase in the private sector.

The development of the retirement age is reflected at the end of the working career. In the public sector, the working career length for people aged 63–68 years increased by one year, and for people aged 53–62 years, by nearly one year.

The lengthening of working careers at the end of working life is primarily because, previously, many public sector employees retired before reaching the age of 63, whereas now, many continue working until they are 64 or older. This development is attributed to the reduction of occupational retirement ages that are lower than the general retirement age and the increase in personal retirement ages that are higher than the general retirement age.

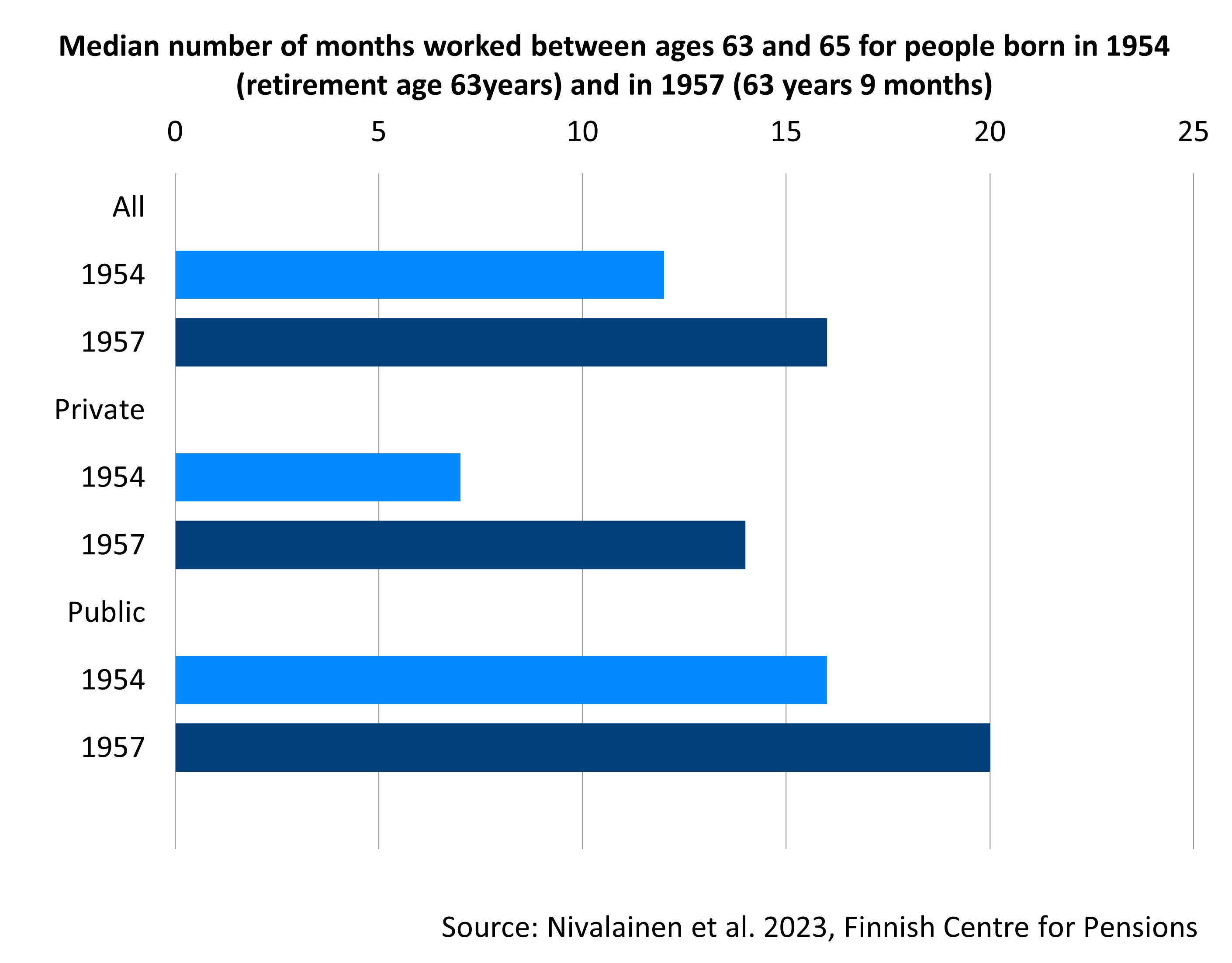

Months worked after the age of 63 has increased due to the rising retirement age

As part of the 2017 pension reform, it was agreed that the retirement age would be gradually increased, one cohort at a time. As a result of this reform, the transition from work to retirement on an old-age pension has been deferred. Consequently, the working careers of those who have continued to work until their retirement age have been extended. Those born in 1957, whose retirement age was 9 months higher than for those born in 1954, worked four months longer between the ages of 63 and 65 than those born in 1954. Thus, the working career length has not increased as much as the retirement age has risen.

In the private sector, the number of months worked within this age range has increased significantly more than in the public sector. However, in the public sector, employees tend to work beyond the age of 63 for a longer period compared to the private sector. The low-educated have experienced longer working career extensions than the high-educated.

The intended retirement age has been clearly delayed since the 2017 pension reform

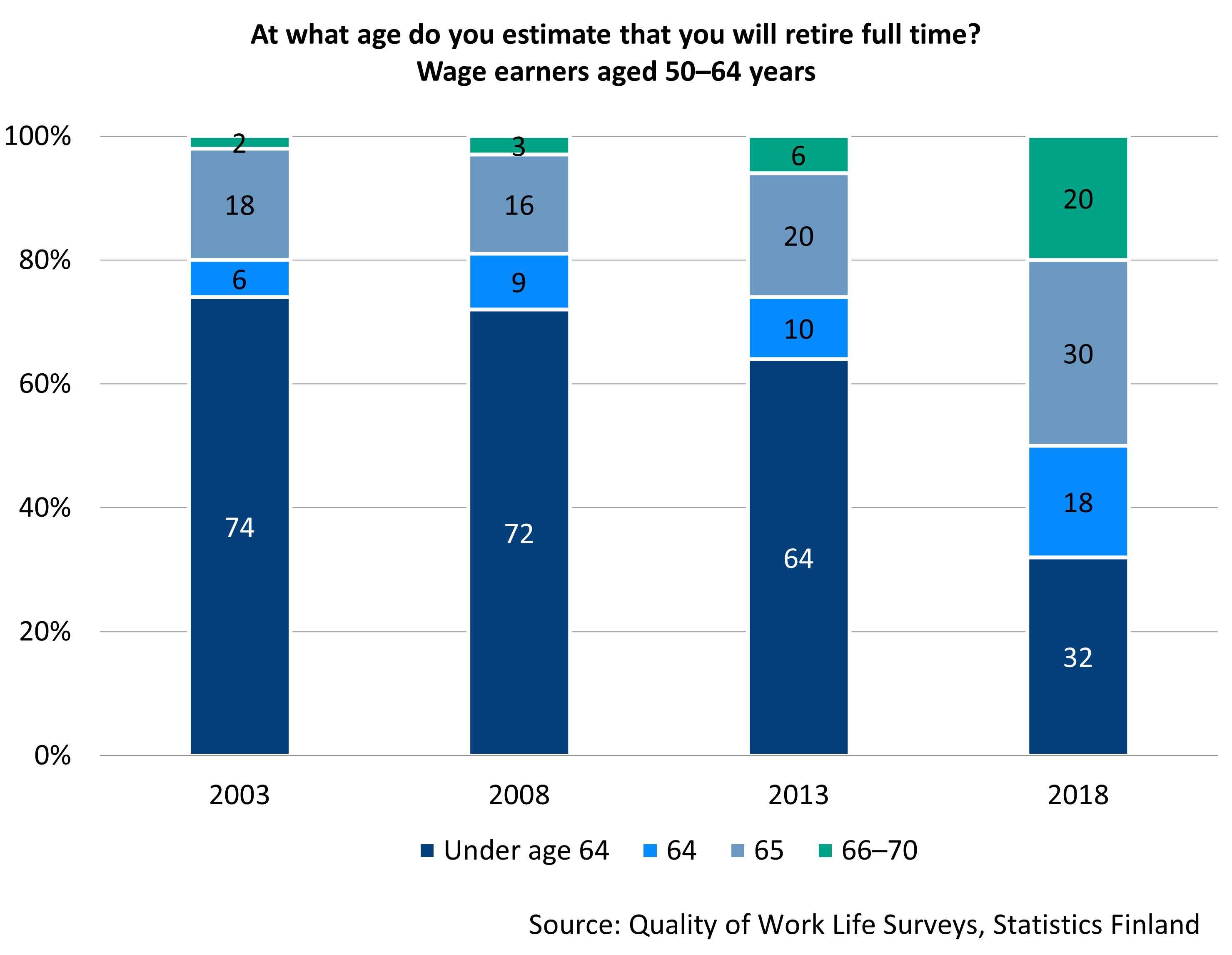

The intended retirement age of employees has been delayed. In 2003, less than 30 per cent of employees aged 50–64 intended to retire full-time at age 64 or older. By 2013, this share had grown to just over one-third.

Since the 2017 pension reform, the intended retirement age has risen significantly faster. By 2018, two-thirds of respondents planned to retire at the age of 64 or older. One-fifth intended to retire no earlier than at age 66.

Publications:

- Nivalainen 2022. Socio-economic differences: retirement and working lives in 2006, 2011 and 2017 (Julkari)

- Nivalainen et al. 2023. Studies on changes in retirement on old-age and disability pension after the 2017 pension reform (Julkari)

- Polvinen et al. 2022 Educational inequalities in employment of Finns aged 60–68 in 2006–2018 (PLoS ONE)

- Riekhoff & Kuitto 2022. Educational differences in extending working lives: Trends in effective exit ages in 16 European countries (Julkari)

Read more on Etk.fi:

An increasing number of people continue working in retirement

The flexible old-age pension offers options for retiring and continuing at work. A working career does not necessarily end with retirement, as some people continue working even while receiving their old-age pension. However, to transition to retirement, the employment relationship must first be terminated.

Working while receiving an old-age pension is unrestricted by income limits, and for any work done while drawing an old-age pension, additional pension accrues up to the age when the obligation to take out pension insurance ends. For those working as self-employed persons while drawing an old-age pension, taking out pension insurance is optional.

The proportion of people working while drawing an old-age pension has increased in recent years. Surveys indicate that in 2017, 14 per cent of old-age pensioners aged 63–74 had worked in the previous 12 months while receiving their pension. In 2020, this figure rose to about 20 per cent.

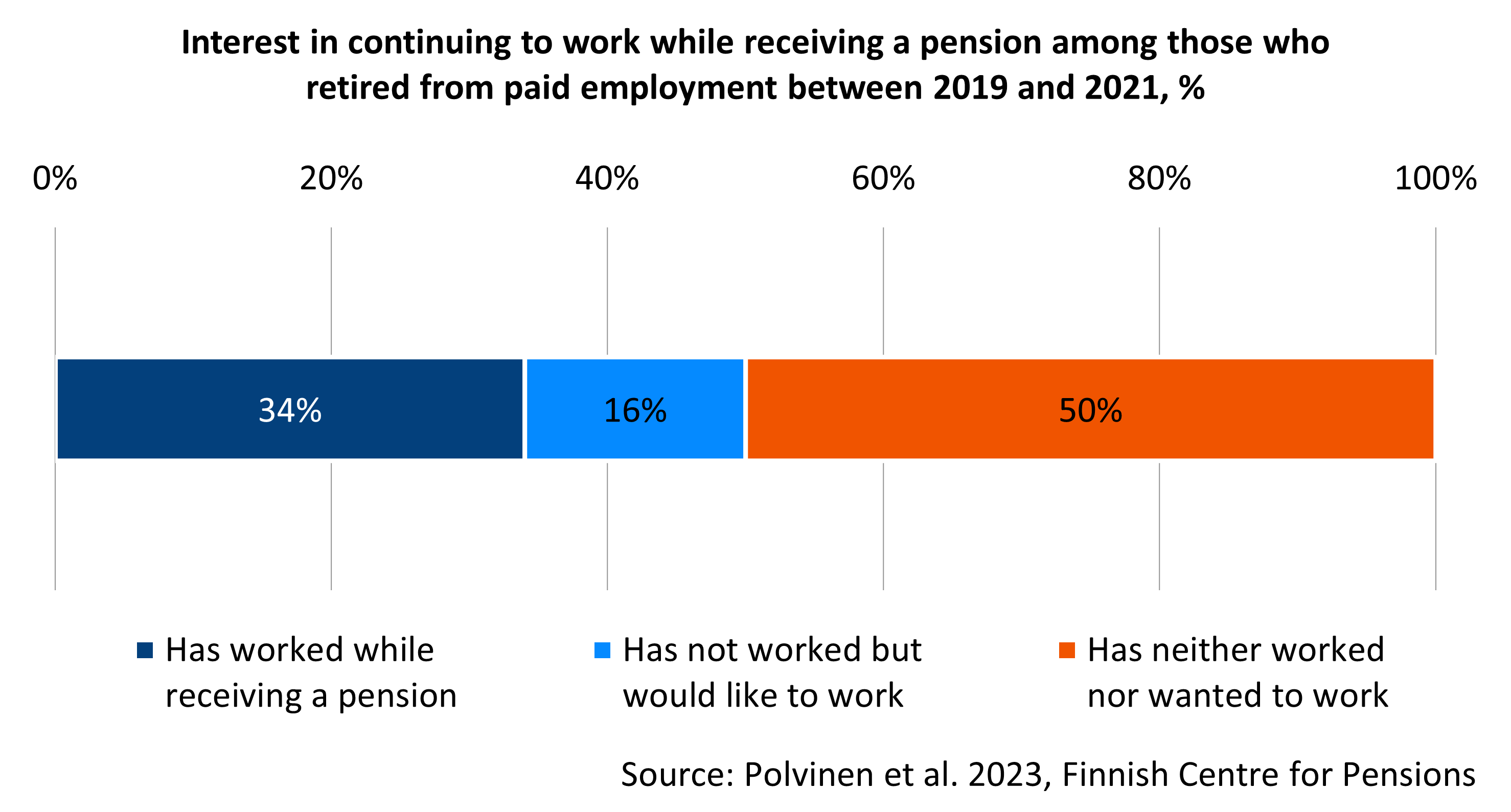

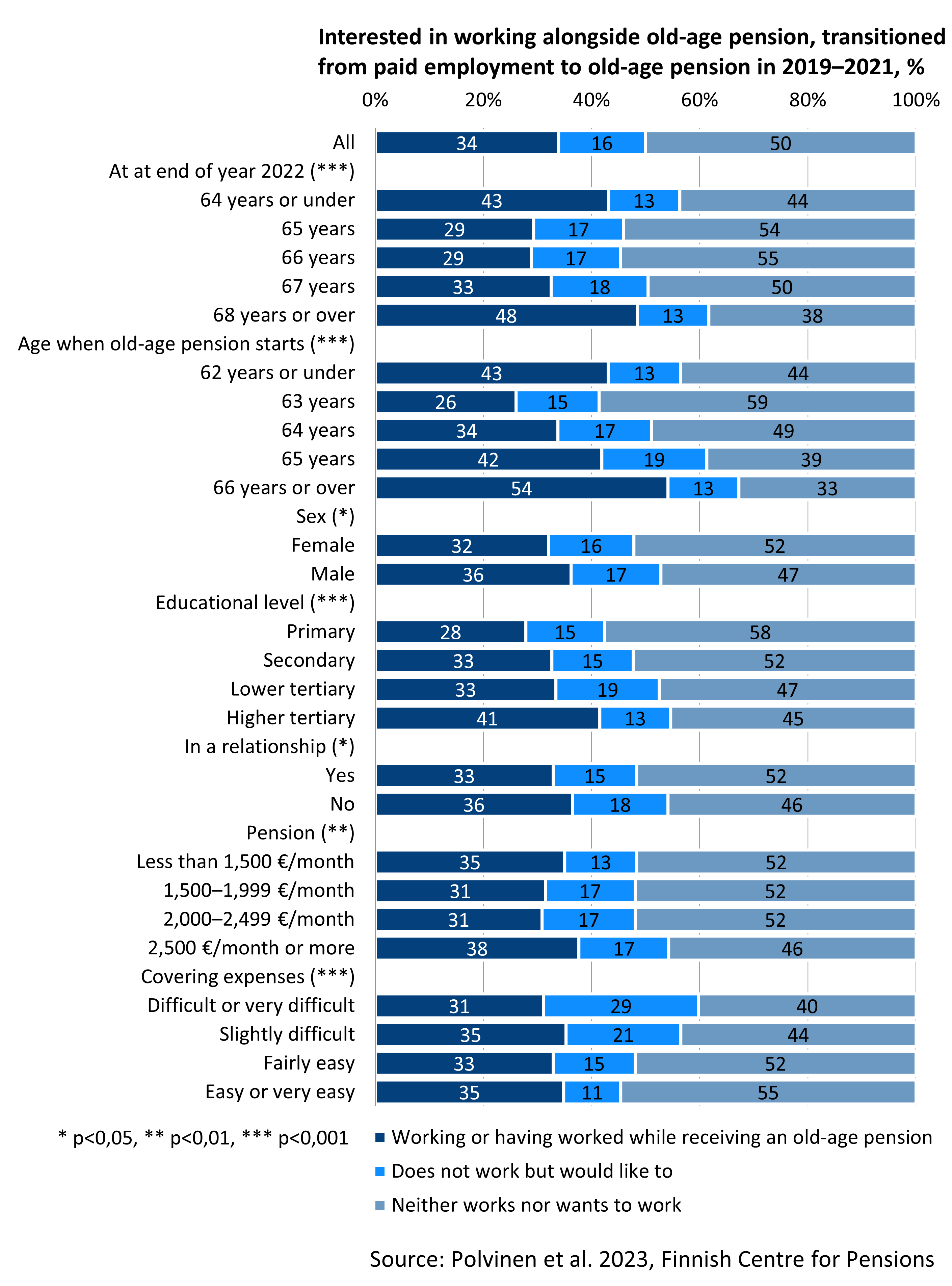

Among those who have recently retired from paid employment, the proportion of those working is even higher. According to a survey conducted in 2022, one-third of those who transitioned from paid employment to old-age pension between 2019 and 2021 reported having worked alongside their pension in the previous 1–3 years. There appears to be broader interest in working while on a pension. 16 per cent had not worked while on a pension but would have liked to. Half of those who retired from paid employment were not interested in working while on a pension.

Differences in working while receiving an old-age pension among different population groups

People who work while receiving an old-age pension often retired later than average. The better their health and ability to work, the more likely they are to work while receiving a pension. In addition, men, the highly-educated and self-employed persons are more likely than others to work while on a pension.

Differences in income also play a role. Low-income people, as well as high-income people, are more likely to work while receiving a pension compared to others. High-income people tend to work for longer periods alongside their pension. For low-income people, working while receiving a pension is often driven by financial necessity, seeking additional income. High-income people are usually motivated by reasons other than financial ones.

Many work-related factors are connected to working while on a pension. Those who continue working during retirement are often the ones who enjoyed their pre-retirement job and felt appreciated at their workplace for their skills as older employees.

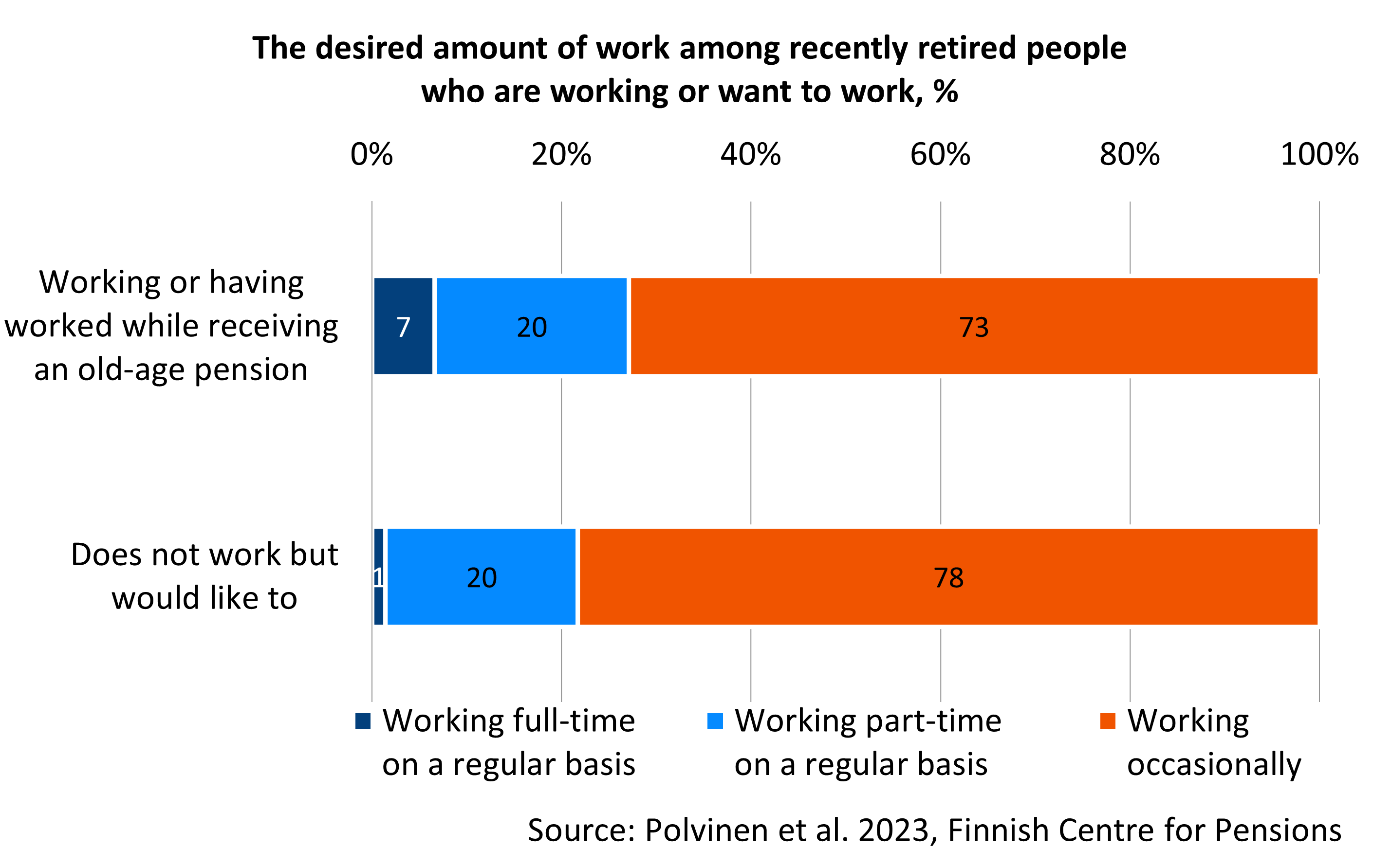

Working while receiving a pension is often irregular or occasional

Working while receiving a pension is often part-time or occasional. Few pensioners want to work full-time on a regular basis.

Many working pensioners continue to work for the same employer and in similar positions as before retirement. Pensioners often work in expert professions and in the healthcare sector.

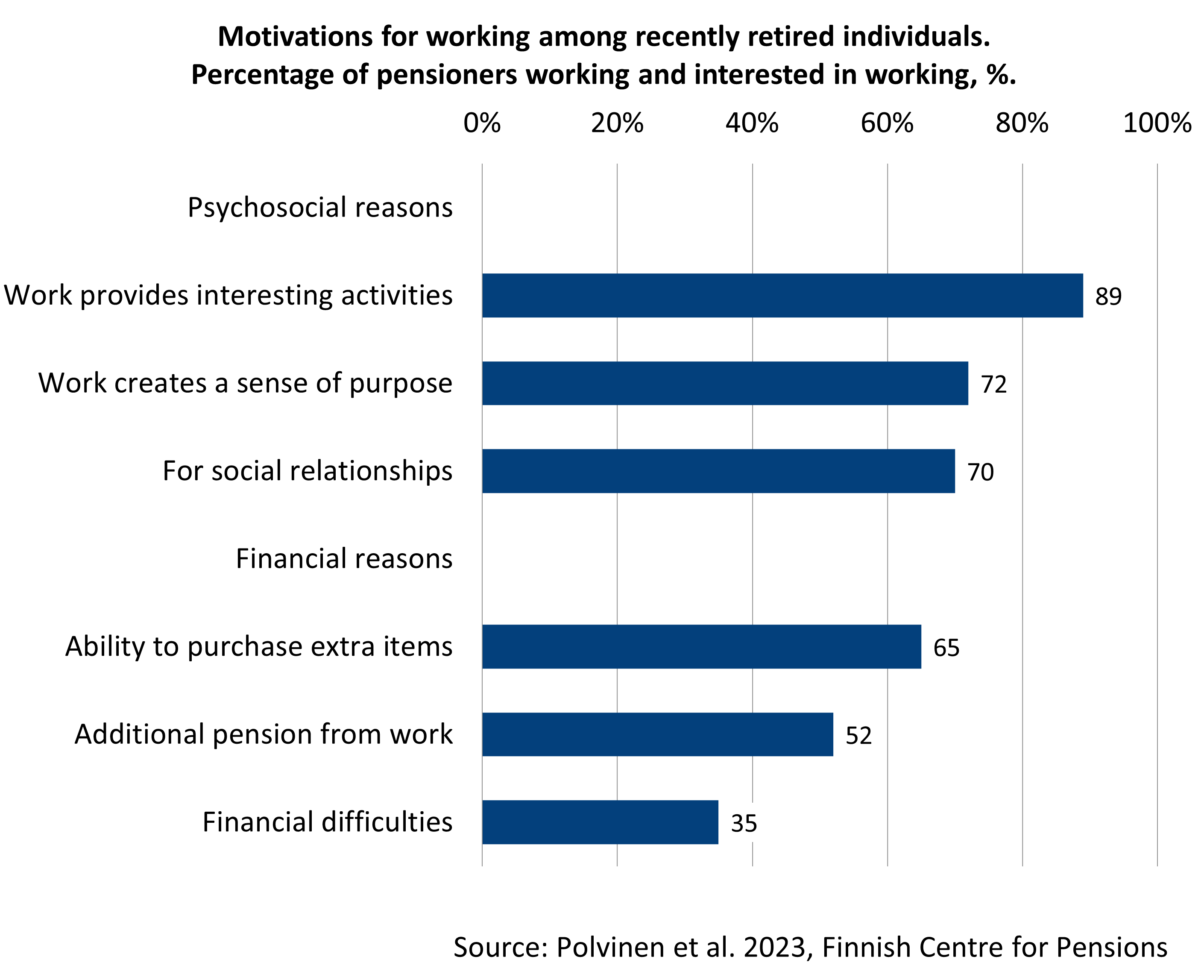

Working in retirement because it provides interesting activities

Retirees often want to work because it provides interesting activities and a sense of purpose. Social relationships and financial factors also play a role. Many choose to work in retirement to be able to make additional purchases. One third of pensioners work because of financial difficulties.

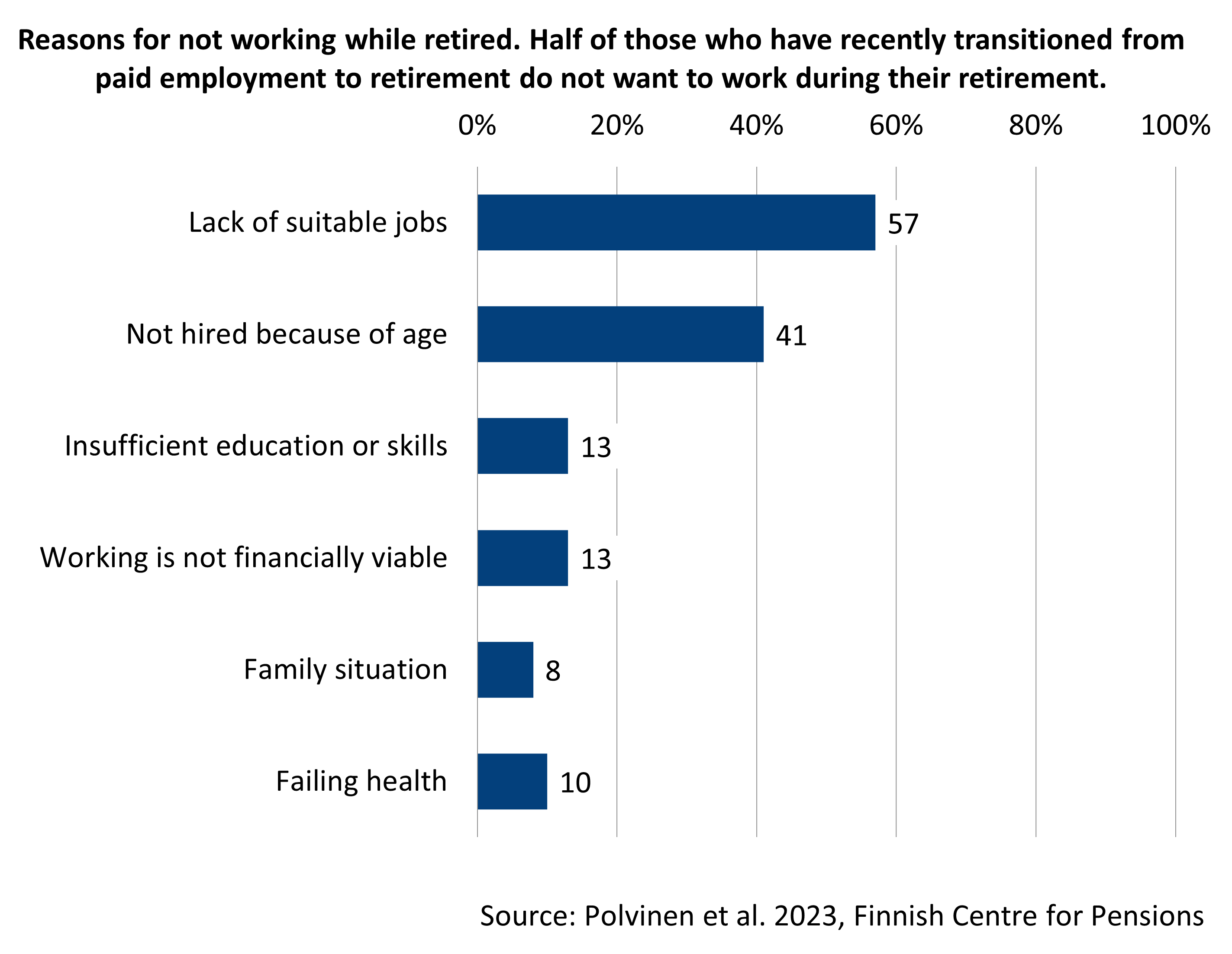

Many pensioners cannot find suitable work

16 per cent of recently retired people would like to work but do not. About half of them feel that suitable jobs are not available or that they will not be hired because of their age. Only a small number feel that they lack the necessary skills or that their health or family situation prevents them from working in retirement.

Graph’s “Reasons for not working while retired.” data in accessible Excel file.

Half of those who have recently transitioned from paid employment to retirement do not want to work in retirement. Almost all say they want to enjoy their retirement and feel they have already had a long enough career.

Publications:

- Polvinen et al. 2024. Patterns of work and retirement in a pension system with a flexible old-age retirement age: a register study of Finnish employees and self-employed persons born in 1949. (Work, Aging and Retirement)

- Polvinen et al. 2023. Working in retirement. Survey of persons retiring from work on an old-age pension in 2019–2021. (Julkari)

- Polvinen et al. 2022. Educational inequalities in employment of Finns aged 60–68 in 2006–2018 (PLoS ONE)

Employers’ perceptions of older workers are increasingly positive

As the population ages, the number of older workers has also risen. In the early 2000s, one in ten workers was aged 55 or over. Today, one in five workers is over 55. Around 15 per cent of workplaces have someone who is already receiving pension benefits.

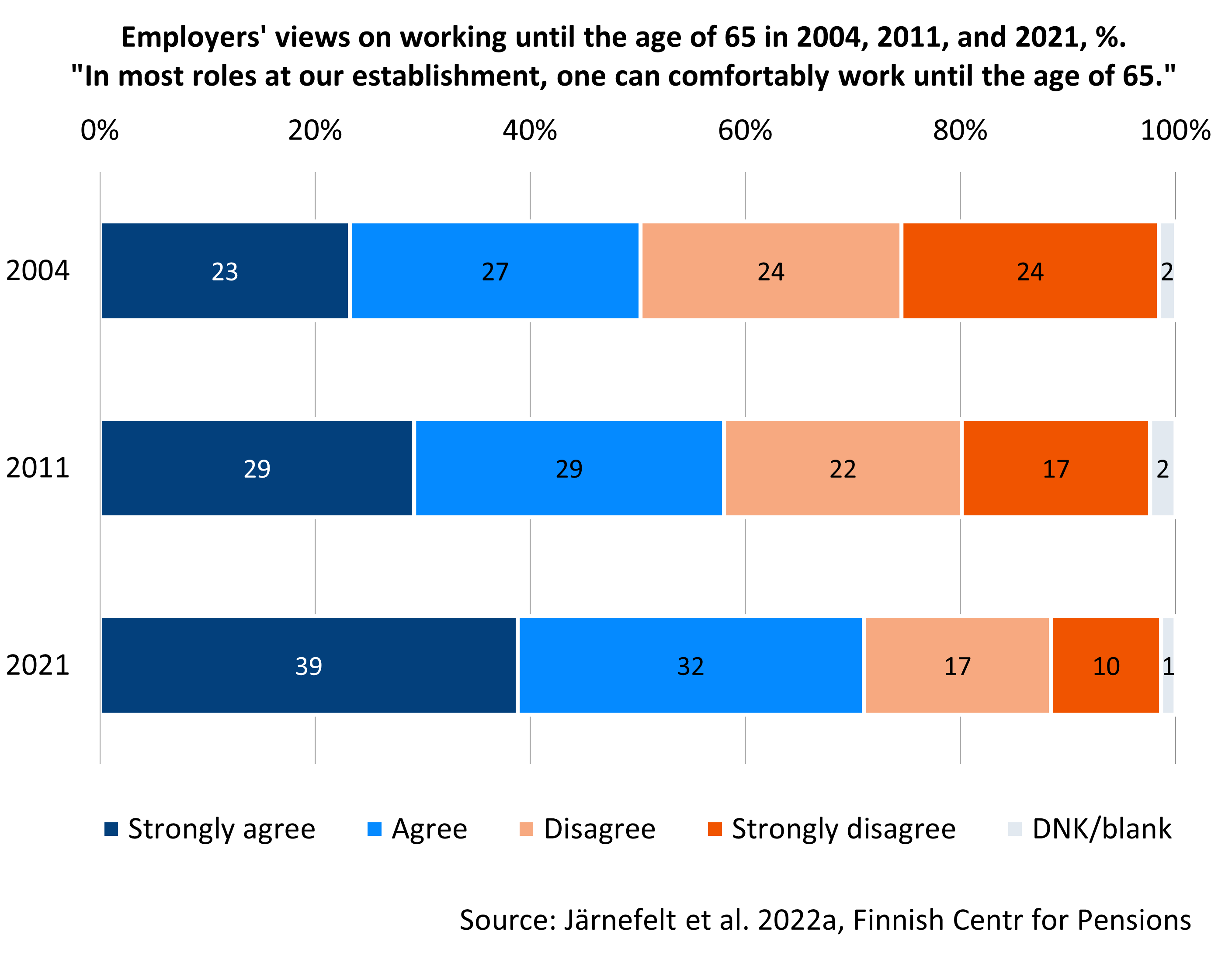

Employers’ views on older workers have become more positive since the early 2000s. More than 70 per cent of employers now believe that most job roles can be performed up to the age of 65. In the early 2000s, only about half of employers held this view.

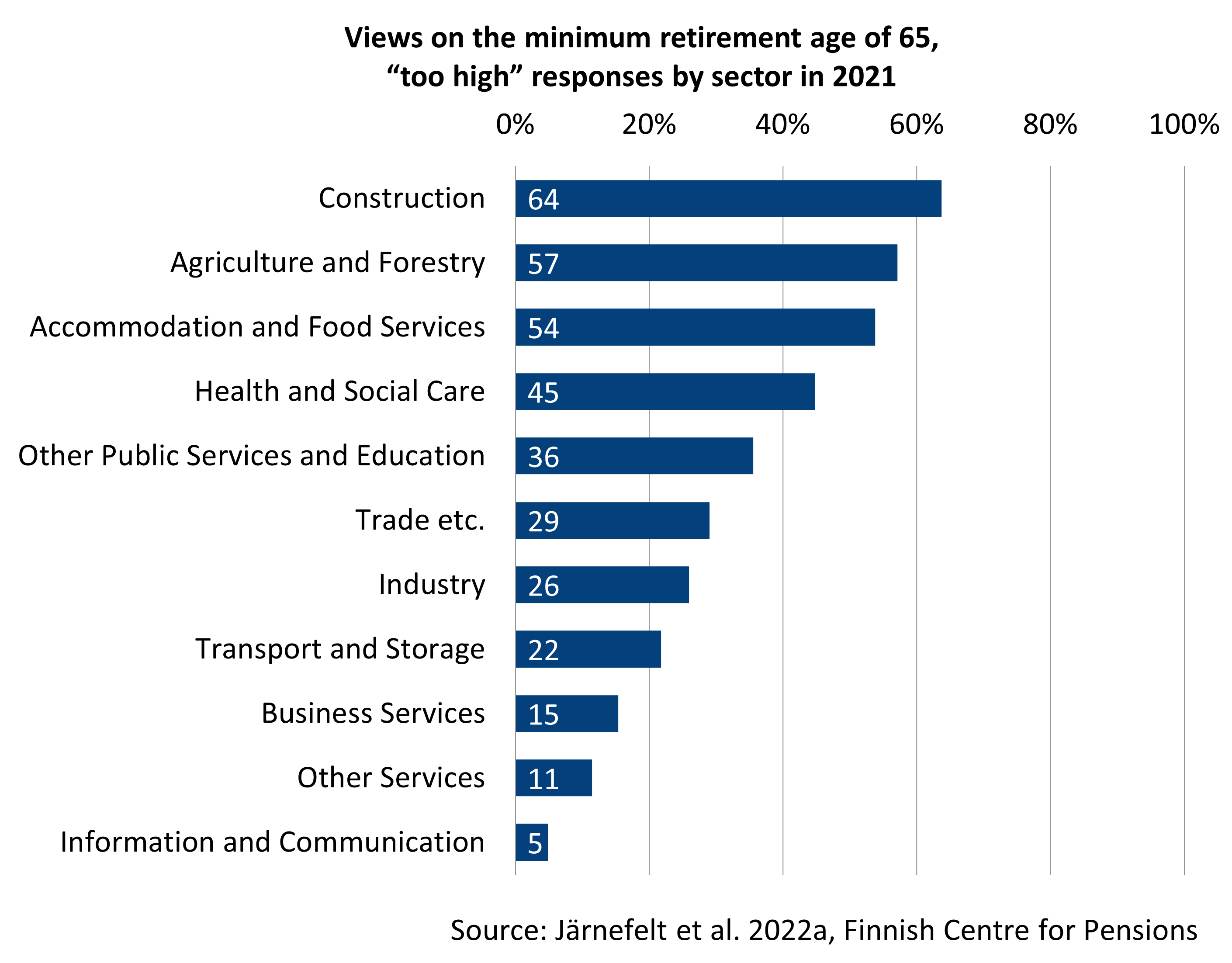

Around two-thirds of employers consider 65 to be an appropriate minimum retirement age. However, there are differences between sectors. For example, more than half of employers in construction, agriculture and forestry, and hotels and restaurants think the minimum age of 65 is too high.

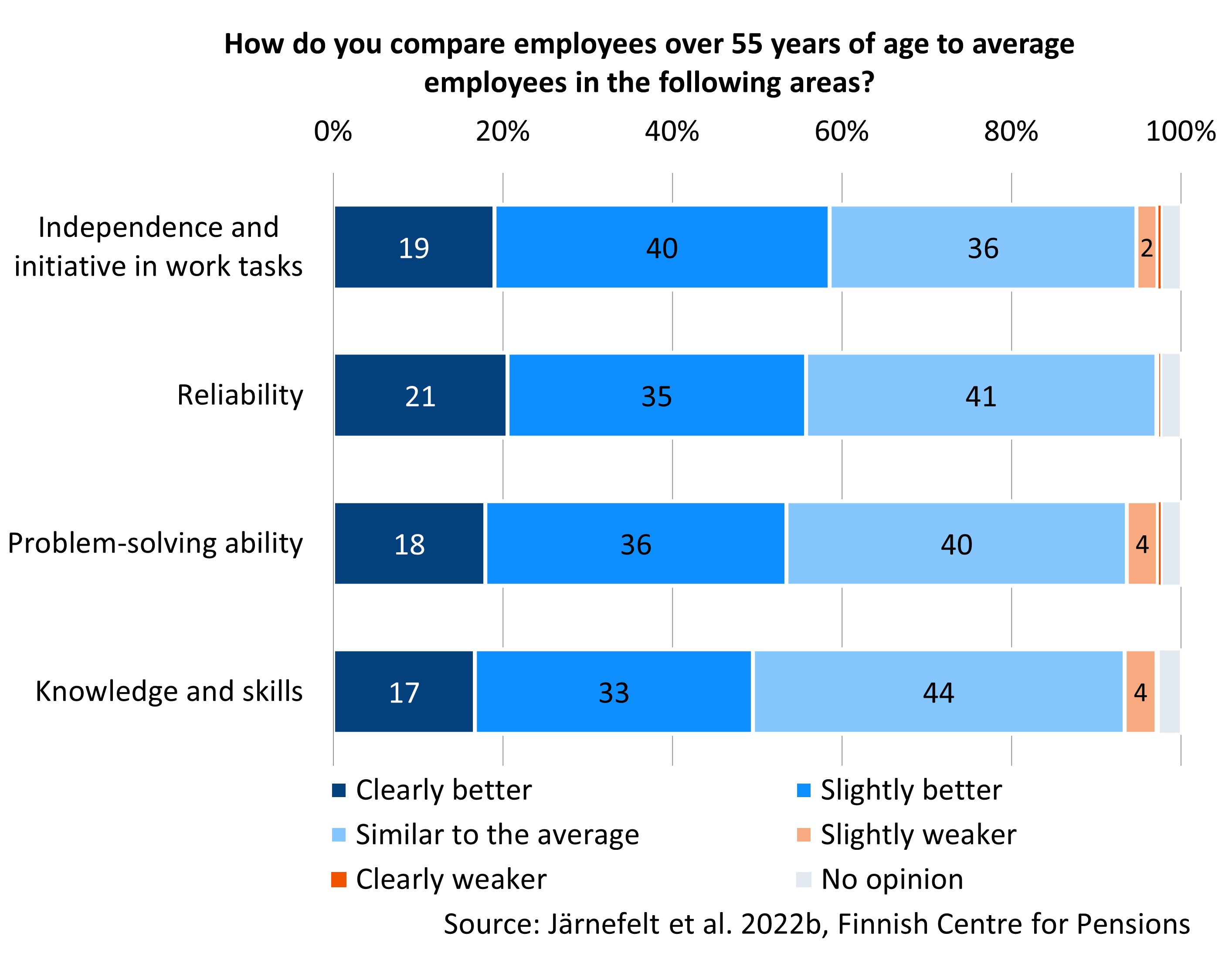

Employers believe that workers aged 55 and over are as good as or better than average workers in terms of independence, initiative, reliability, problem-solving skills and knowledge and skills. On the other hand, health and functional problems as well as outdated skills are seen as a barrier to hiring people over 55.

Almost 80 per cent of employers believe they can hire someone over 55 as a new employee. The willingness to hire older workers has increased since 2011. The private sector is less interested in hiring older workers than the public sector.

Although most employers have positive attitudes towards hiring older workers, negative age stereotypes still hold some employers back. Even employers facing recruitment difficulties may not be more likely to hire people over 55 if they have negative perceptions of older workers.

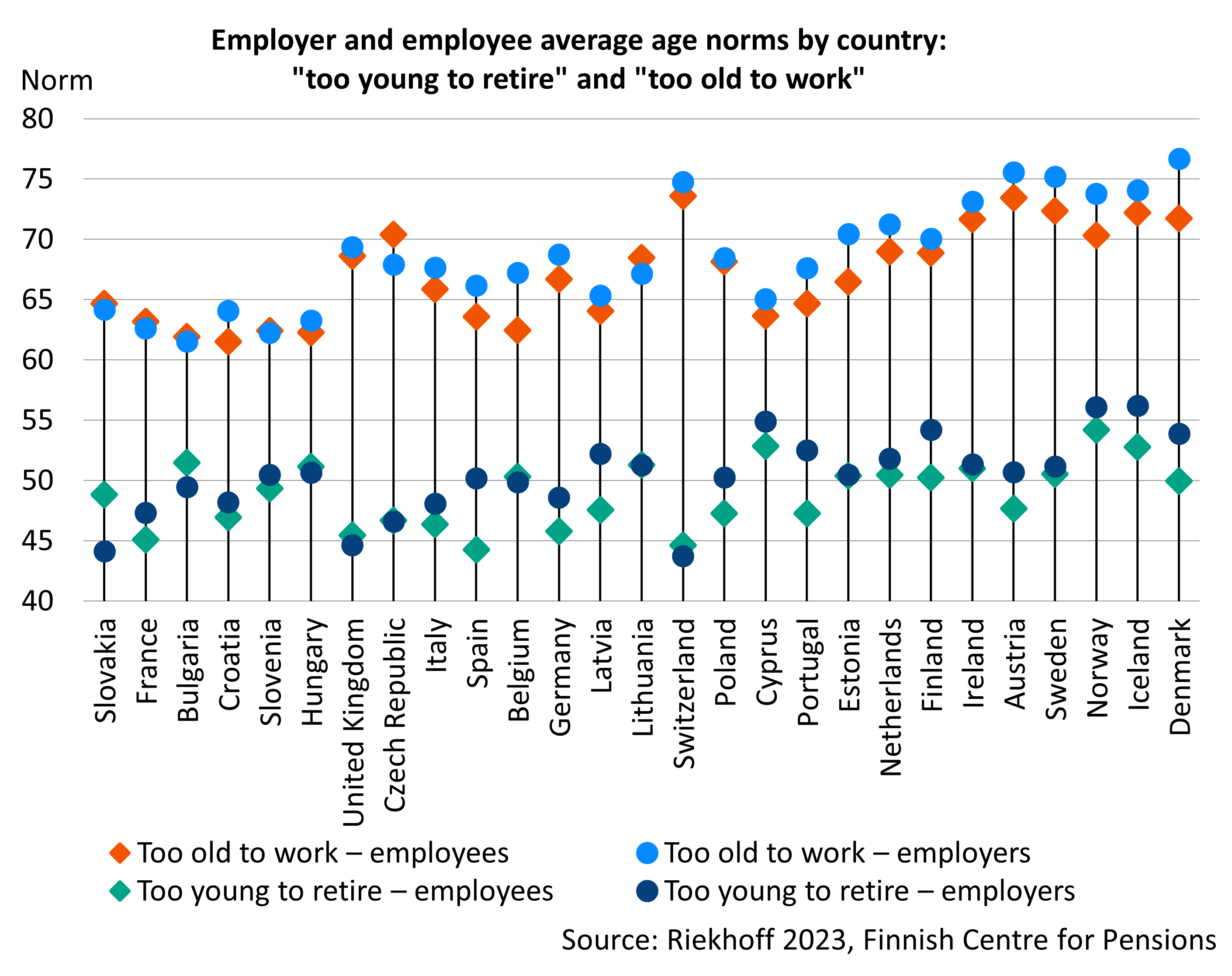

In Finland, employers consider the appropriate retirement age to be higher than the European average

Finnish employers generally believe that 70 is too old to work. Although their views on the appropriate retirement age are higher than the European average, they are still lower than in other Nordic countries.

These perceptions of appropriate working ages are referred to as age norms. Employers’ retirement age norms are often higher than those of employees. Cultural attitudes towards age play an important role in shaping these norms, as employers’ and employees’ perceptions of the appropriate retirement age are generally similar within countries. Moreover, retirement age norms are linked to the statutory retirement age: norms tend to be higher in countries where the statutory retirement age is relatively high.

Most young people work between the ages of 17 and 22

- Järnefelt et al. 2022. Employers’ perceptions of over-55-year-old employees, support for continued working and obstacles to hiring (Julkari)

- Järnefelt et al. 2022. Employer’s views on retirement age and extending working lives. Results of employer survey in 2004, 2011 and 2021. (Julkari)

- Riekhoff 2023. Employers’ retirement age norms in European comparison (Work, Aging and Retirement)

- Riekhoff et al. 2023. Labour shortages and employer preferences in retaining and recruiting older workers (International Journal of Manpower (ahead-of-print). | Accepted manuscript version.

Early and mid-stages of a working career

The early and middle stages of a person’s working career are crucial for the development of their entire working career. A significant number of young people work and accumulate some pension rights between the ages of 17 and 22. Career breaks related to starting a family are still significantly longer for women than for men. Disability shortens the working careers particularly of the less educated.

Most young people work between the ages of 17 and 22

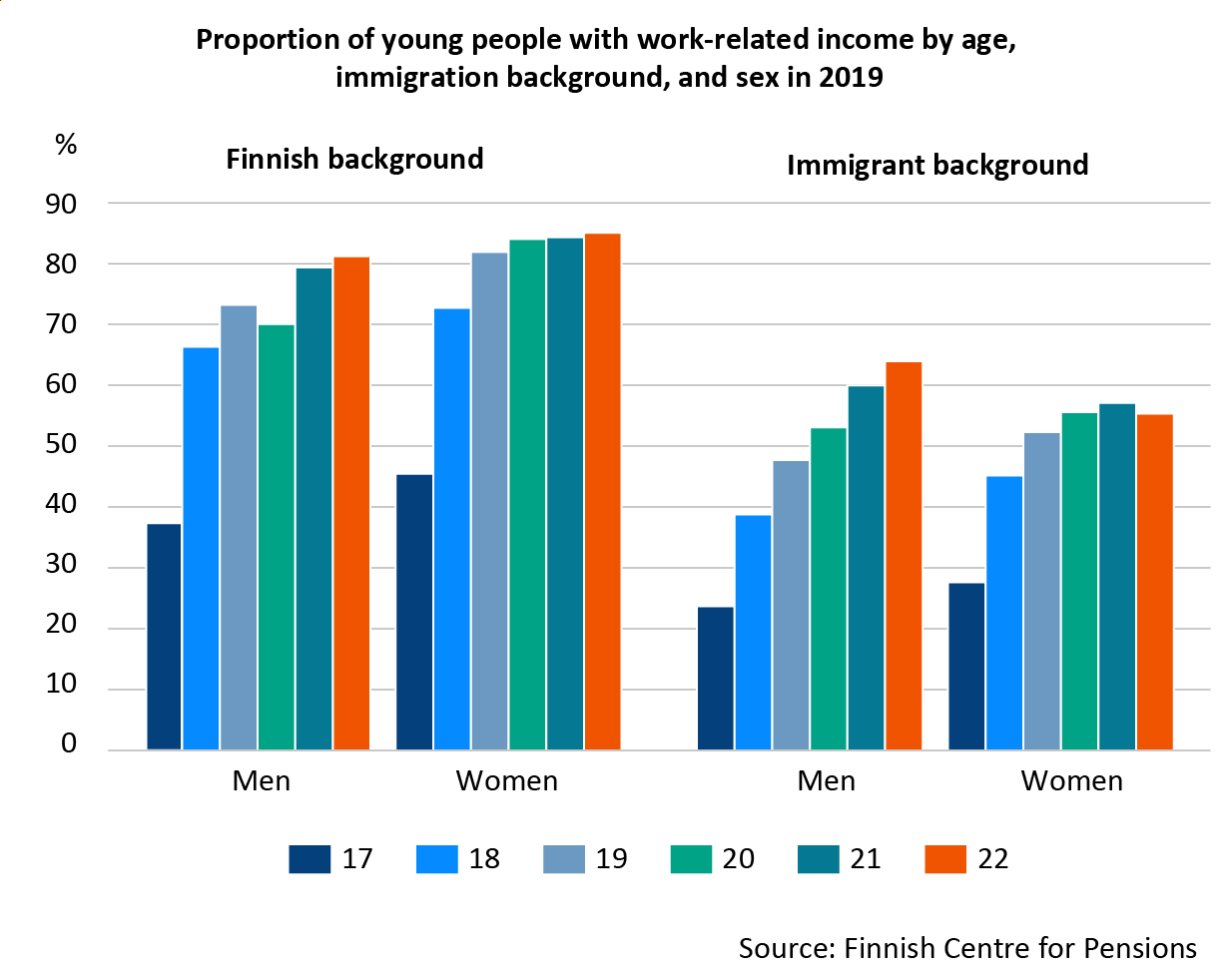

Around three-quarters of 19-year-olds worked at least to some extent in 2019. Employment is often part-time, temporary and seasonal, but becomes more common and earnings increase with age.

Young women work more often than young men. This difference decreases with age, and by the age of 22 there is no gender gap in the number of months worked. Most young people work in the private sector, while even at the beginning of their careers, more women than men work in the public sector.

Young people with a migrant background are less likely to work than those with a Finnish background. Differences in employment and earnings between those with a migrant background and those with a Finnish background are already apparent in the early stages of their working careers. For men, these differences in employment rates decrease somewhat with age, but for women there is little change.

Early stages of working career relevant for pensions

The minimum age for pension accrual was lowered in the 2005 reform from 23 to 18 years, and further to 17 years in the 2017 reform. As a result of these changes, work done at a young age now contributes more to pensions.

Among those born between 1992 and 1996, on average only just under 9 per cent did not work at all between the ages of 18 and 22. For those born in 1996, the average (median) pension accrued from earnings between the ages of 18 and 22 was 47 euros per month. In the highest income decile, the corresponding accrual was 120 euros per month. The lowering of the minimum age for accruing a pension has thus boosted pension income for most young people.

In Finland, pensions are accrued during most of the working career. However, in a European comparison, the Finnish pension system for young people stands out in three respects: the start of pension accrual is later, pension benefits are earned for education, and compulsory military service does not contribute to pension accrual. In most countries there is no minimum age for pension accrual.

Publications:

- Ilmakunnas et al. 2021. Work and pension accrual of young Finns from the point of view of the 2005 and 2017 pension reforms. (Julkari)

- Hofäcker & Kuitto (eds.) 2023. Youth Employment Insecurity and Pension Adequacy. (Edward Elgar Publishing)

- Kuivalainen et al. 2023. Youth and pensions in European comparison – how pension systems consider early adulthood and life course uncertainties (Julkari)

- Lorentzen et al. 2019. Pathways to adulthood: Sequences in the school-to-work transition in Finland, Norway and Sweden. (Springer Link)

- Saloniemi et al. 2020. The diversity of transitions during early adulthood in the Finnish labour market (Journal of Youth Studies)

The high concentration of family leaves to mothers and the strong gender segregation in the labour market contribute to gender gaps in careers. While young men and women have similar rates of attachment to the labour market, there are significant differences in earnings from the start of their careers. For those born in 1980, women’s average earnings were only 70 per cent of men’s by the age of 36, although there was no significant difference in length of employment.

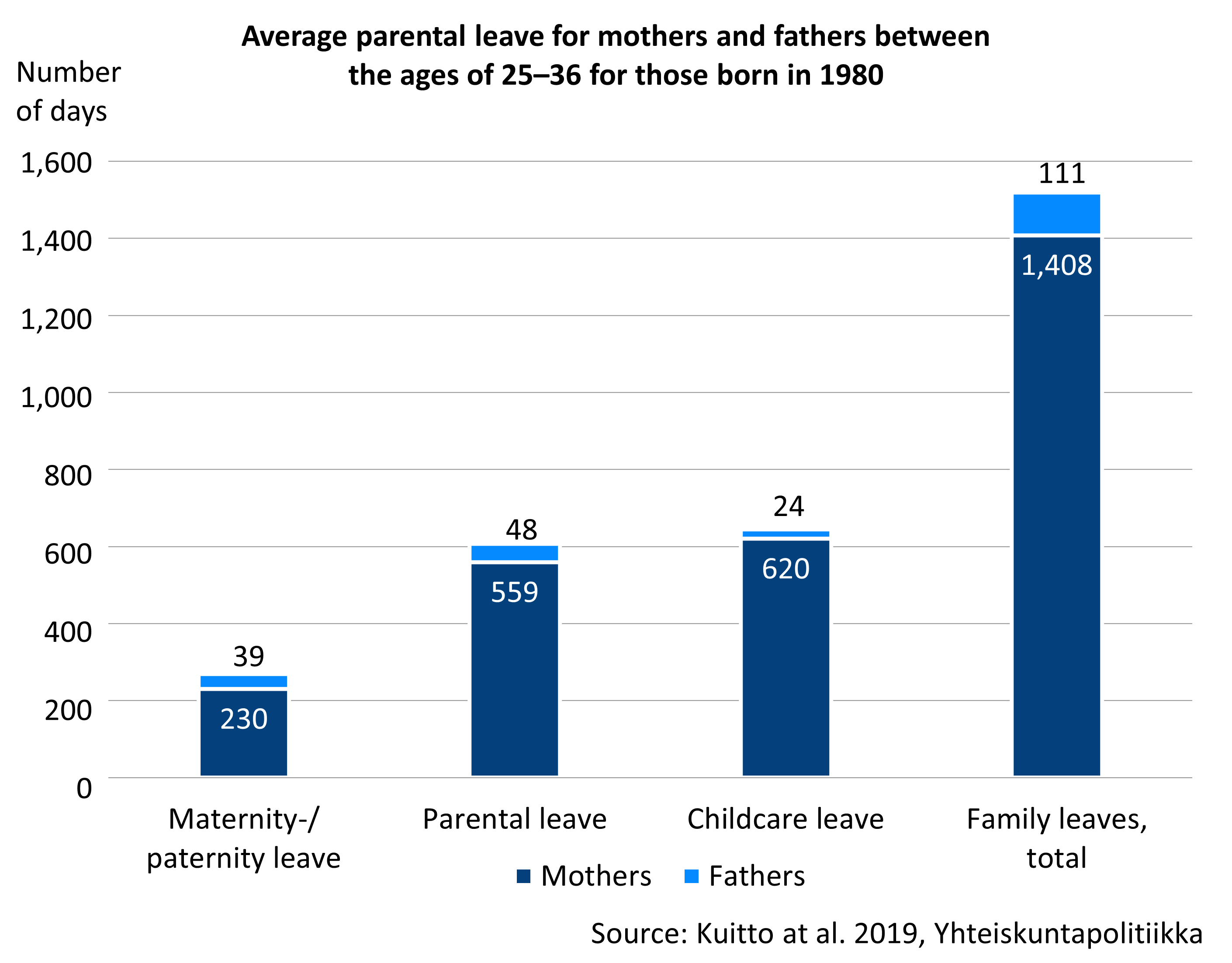

Career breaks due to family leave are significantly longer for women than for men. Mothers born in 1980 took 13 times more days of family leaves than fathers. Long periods of child home care allowance, especially for mothers in lower socio-economic groups, are a unique feature of Finnish family policy in European comparison.

The significant gender gap in career breaks due to family leave mainly affects the labour market status and earnings of women with lower education and immigrant backgrounds. Although family leaves contribute to pension benefits, longer periods of family leave, especially those on

Publications:

- Kuitto ym. 2019. Perhevapaat työurariskinä? Trajektorianalyysi nuorten aikuisten työurapoluista. (Yhteiskuntapolitiikka)

- Kuivalainen et al. 2019. Naisten ja miesten eläke-erot : Katsaus tutkimukseen ja tilastoihin. (Julkaisuarkisto Valto)

- Kuitto & Kuivalainen 2021. Gender inequalities in family leaves, employment and pensions in Finland. (Edward Elgar)

Retirement on a disability pension shortens working careers

Incapacity for work can lead to a premature end to a working career. Every year, around 20,000 people retire on a disability pension. By the end of 2022, about 5.3 per cent of the working-age population received a disability pension.

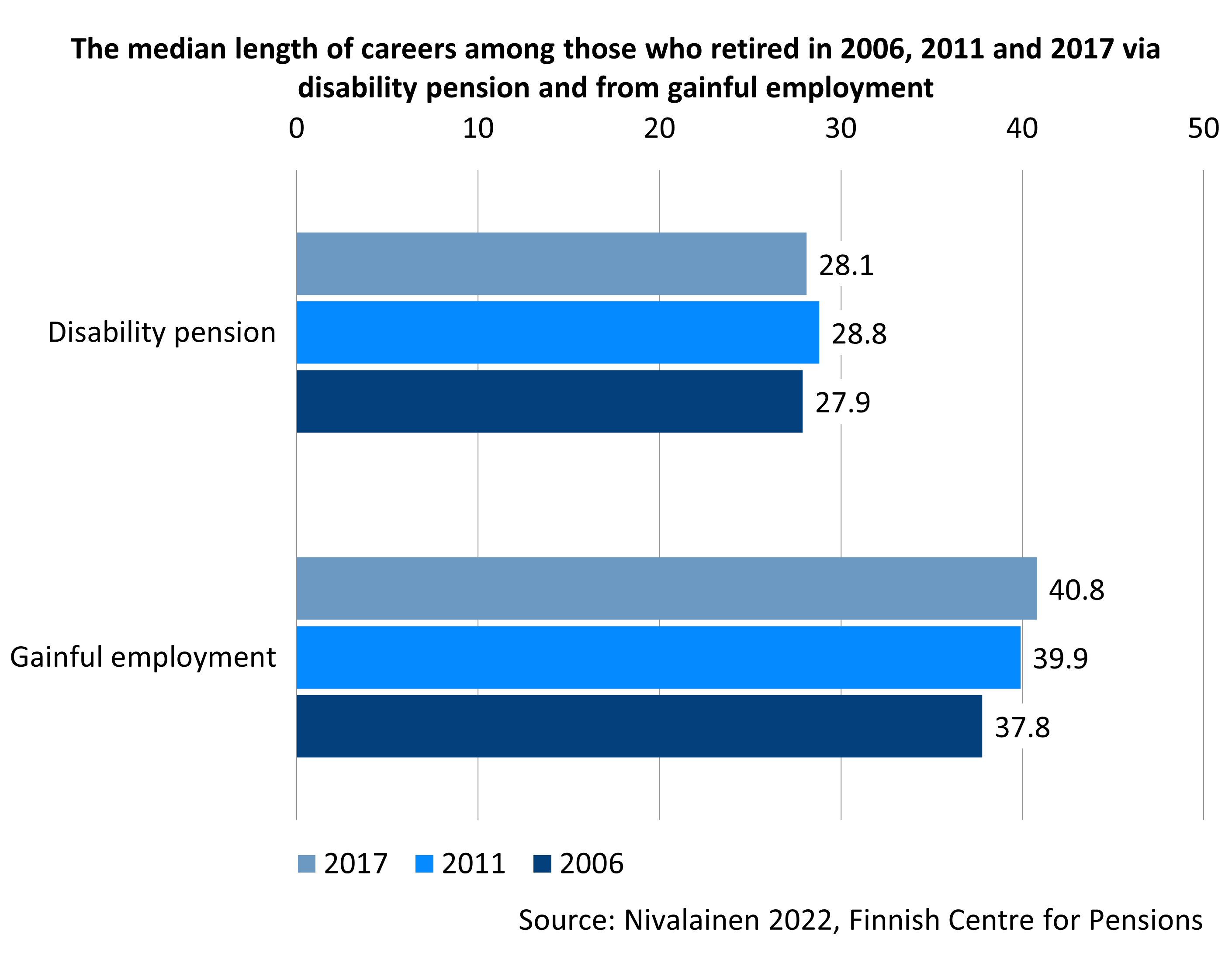

Retirement on a disability pension shortens working careers. In 2017, those who retired via a disability pension had a median career length of 28.1 years, compared with 40.8 years for those who retired directly from work. Between 2006 and 2017, there was little change in the career length of those who transitioned from a disability pension to an old-age pension.

The transition to a disability pension is more frequent among those with basic and intermediate education than among those with higher education. There are also differences between these educational groups in terms of the length of time spent on disability pensions. On average, the less educated spend more time on disability pensions than the highly educated.

Proportion of people returning to work from temporary disability pension has increased

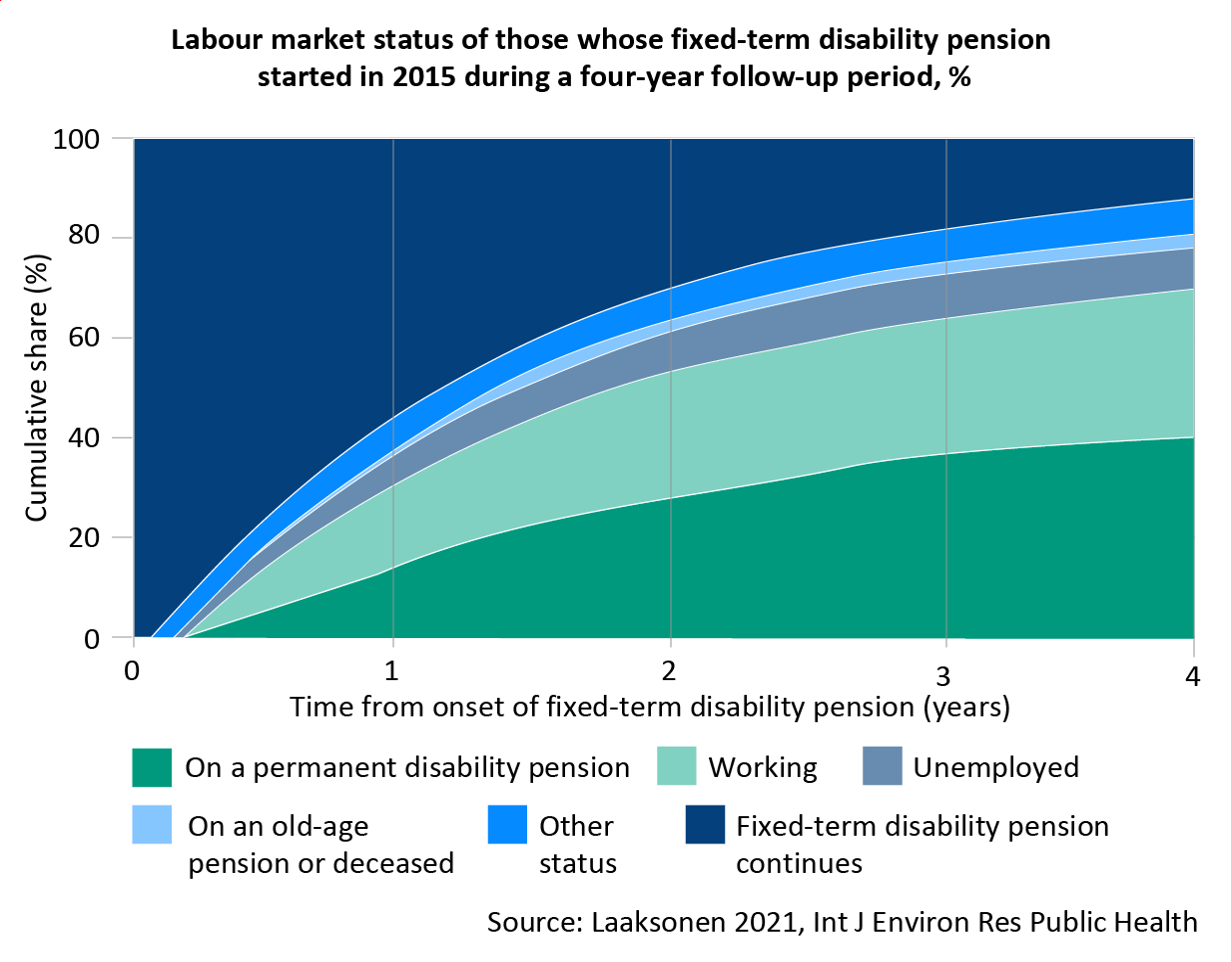

In Finland, a disability pension can be granted either as a temporary disability pension (also referred to as a cash rehabilitation benefit) or as a permanent disability pension. During the period of receiving a temporary disability pension, the aim is to help the recipient to recover and return to work and continue their working career. The share of granted temporary disability pensions of all granted disability pensions has increased in recent years. Today, more than half of new disability pensions are granted as temporary disability pensions.

The proportion of people returning to work from a temporary disability pension has increased somewhat in recent years. In 2015, 30 per cent of those who transitioned to a temporary disability pension returned to work within a four-year follow-up period, compared to 24 per cent ten years earlier. Nevertheless, most temporary disability pensions continue to be converted into permanent disability pensions. Younger age, higher education and employment before transitioning to a temporary disability pension are associated with a higher likelihood of returning to work.

Many partial disability pensioners continue to work alongside their pension

The share of partial disability pensions has increased in recent years. Today, almost one third of all new disability pensions are granted as partial disability pensions. The aim of partial disability pensions is to enable people to continue working part-time despite a reduced capacity to work. However, people do not have to work to receive a partial disability pension.

About 80 per cent of those receiving a partial disability pension work alongside their pension. Working alongside a full disability pension is also possible, but less common.

Partial disability pensions have become more common, especially for people over 60. They usually last for a few years and often end when the person transitions to an old-age pension. Most recipients of a partial disability pension continue to work throughout the pension period. However, there are differences in employment status depending on factors such as previous labour market status and level of education.

Median duration of partial disability pensions and prevalence of employment during the pension period. Data from partial disability pensions that ended in 2020, N=5,742

| All | 2.6 | 83.9 |

| Employment status before the pension and level of education | Duration of the pension, years, median | Working during the pension period, % |

|---|---|---|

| Employed in the private sector | 2.4 | 85.3 |

| Employed in the public sector | 2.5 | 96.1 |

| Self-employed person | 3.1 | 73.6 |

| Not employed | 2.9 | 30.2 |

| Primary education | 3.0 | 75.9 |

| Secondary education | 2.7 | 83.5 |

| Lower higher educational level | 2.3 | 87.2 |

| Upper higher educational level | 1.9 | 90.3 |

Publications:

- Laaksonen 2021. Work Resumption after a Fixed-Term Disability Pension: Changes over Time during a Period of Decreasing Incidence of Disability Retirement (Julkari) (Int J Environ Res Public Health)

- Laaksonen et al. 2018. Educational differences in years of working life lost due to disability retirement (European Journal of Public Health)

- Nivalainen 2022. Socio-economic differences: retirement and working lives in 2006, 2011 and 2017 (Julkari)

- Polvinen et al. 2023. Osatyökyvyttömyyseläkeläisten työssäkäynti ja ansiotyön merkitys toimeentulossa (Työpoliittinen aikakauskirja)

- Polvinen et al. 2018. Working while on a disability pension in Finland: Association of diagnosis and financial factors to employment (Scandinavian Journal of Public Health)

Read more on Etk.fi:

Changes in labour market

Despite changes in the labour market, working careers in Finland have not clearly become more unstable. However, part-time work, self-employment, combining two or more jobs and changing jobs have become more common in recent years.

Working careers have remained relatively stable

The labour market is constantly evolving. Contrary to what is often claimed, research does not clearly show that working careers in Finland have become more unstable or fragmented than in the past.

Career stability and fragmentation are measured, for example, by the number of months worked in a year. For younger workers in particular, career stability measured in this way has increased between the 1980s and the 2010s.

Working career stability can also be assessed by measuring the length of time people spend outside the labour force. It depends largely on economic cycles, but between the 1960s and the early 2000s, the number of years spent outside the labour force did not change significantly.

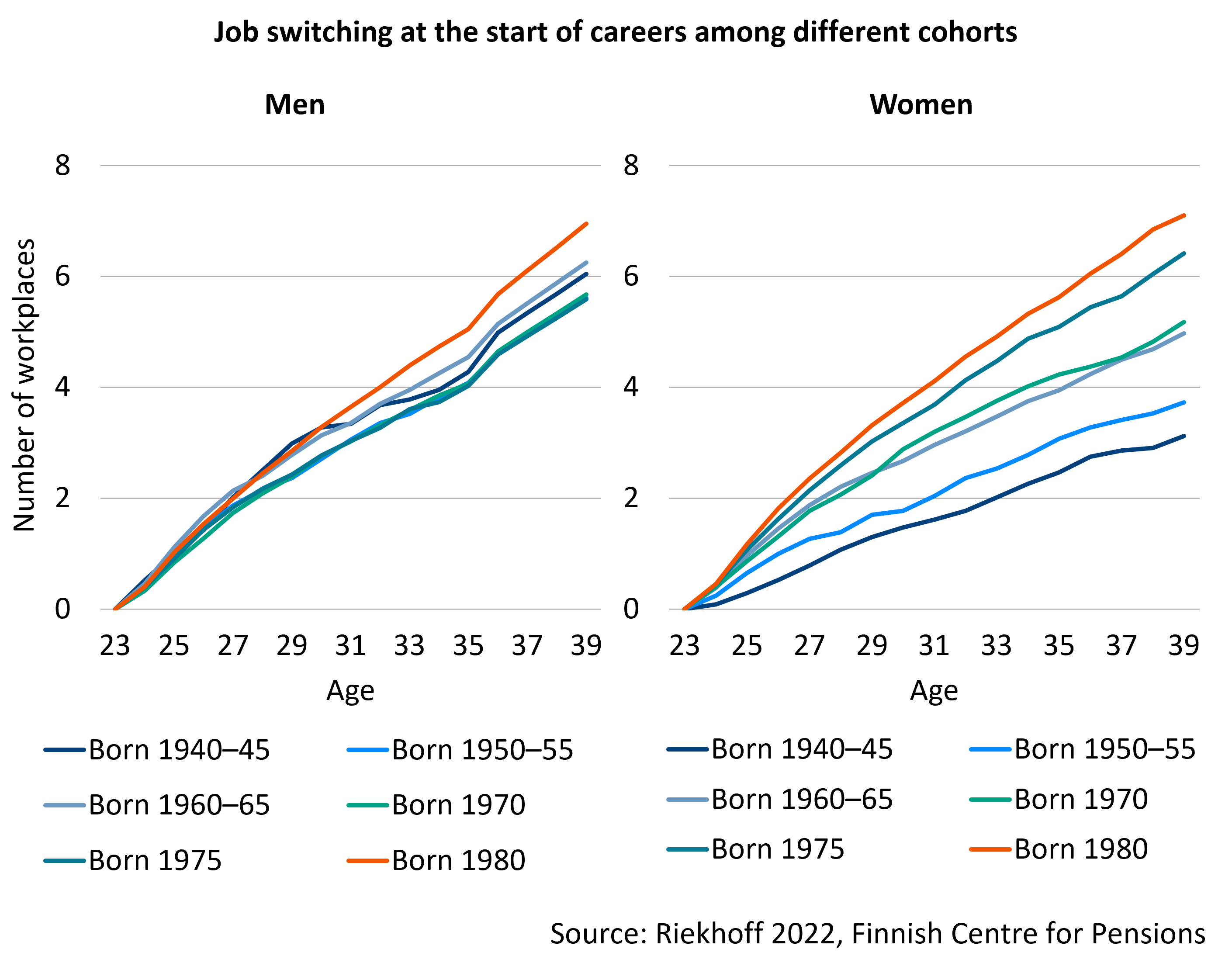

Another dimension of career stability is the frequency with which people change jobs. Since the 1970s, there has been an increase in job changes in the early stages of working careers, especially among women. This change can be voluntary or involuntary. For women, job changes have increased when comparing the cohorts born between 1940 and 1980, while for men, job changes between the ages of 20 and 30 have been almost equally frequent across all age groups.

Stability can also be assessed in a multidimensional way by looking simultaneously at the number of different labour market statuses, their duration and the transitions between them at a given career stage. Based on these so-called turbulence indicators, career paths have remained relatively stable in their middle and later stages across different birth cohorts.

Differences in career stability between genders and socio-economic groups

Although working careers have remained relatively stable over time and across birth cohorts, there are significant differences between genders and socio-economic groups. Women’s careers tend to be less stable than men’s, often due to early and mid-career interruptions related to family responsibilities.

Working careers tend to be less stable in lower socio-economic groups. This is due to a higher risk of unemployment and disability in certain occupations. In addition, women with lower levels of education often experience longer career breaks, particularly in relation to childcare responsibilities.

The instability of working careers affects earnings and hence pension accrual

The Finnish pension system takes account of the instability of working careers. A change of employer does not affect the pension accrued, as is the case in many other countries – it remains intact. Various career breaks, such as unemployment and family leaves, also contribute to pension accrual. However, these career breaks are associated with slower earnings growth later in the working career, which may ultimately result in lower pensions compared to an uninterrupted career.

Changing jobs is increasingly associated with stronger earnings growth, but this seems to benefit mainly men and those with higher education. For women and the less educated, staying with the same employer may be a better way to achieve steady income growth.

Publications:

- Järnefelt 2016. Working Conditions and Working Lives – Research on the Stability of Working Lives and Retirement (Julkari)

- Kuitto ym. 2019. Perhevapaat työurariskinä? Trajektorianalyysi nuorten aikuisten työurapoluista. (Yhteiskuntapolitiikka)

- Riekhoff 2018. Extended working lives and late-career destabilisation: A longitudinal study of Finnish register data. (Advances in Life Course Research) | Accepted manuscript version.

- Riekhoff 2022. Good or bad (in)stability? : A cross-cohort study of the relation between career stability and earnings mobility in Finland (Research in Social Stratification and Mobility

- Riekhoff et al. 2021. Career stability in turbulent times: A cross-cohort study of mid-careers in Finland. (Acta Sociologica) | Accepted manuscript version.

- Ojala et al. 2021. Career Stability in 14 Finnish Industrial Employee Cohorts in 1988-2015 https://www.julkari.fi/handle/10024/140793 (Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies)

Read more on Etk.fi:

Atypical work continues to grow

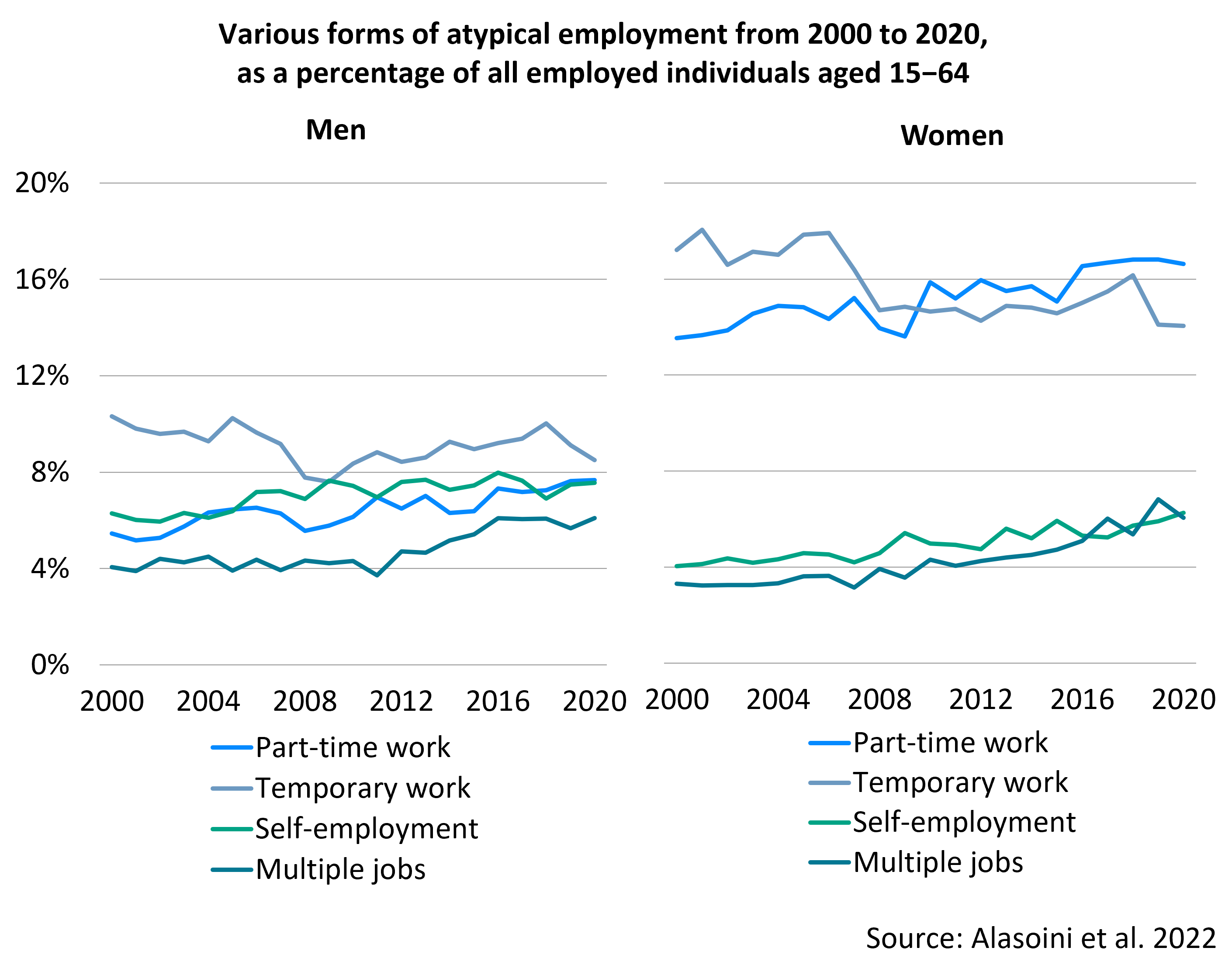

Atypical work refers to work that differs from a full-time permanent job. Among people of working age, part-time and temporary jobs are more common for women than for men: in 2020, around 8 per cent of men had a part-time job and 8 per cent had a temporary job, while for women these figures were around 17 and 14 per cent respectively. The proportions of both part-time and temporary employment have remained relatively stable since the early 2000s, although part-time contracts have increased recently. Temporary contracts are more common in Finland than in other Nordic countries, while part-time work is less common. Other forms of atypical work, such as self-employment, combining two or more jobs and working through temporary employment agencies, have become more common in recent years.

Atypical work can affect pension level

Pension accrual is directly proportional to earnings, which means that in part-time work, where earnings are lower than in full-time work, pension accrual is also lower. Temporary contracts have been shown to reduce opportunities for internal training and career development. In addition, poorer working conditions may accelerate the transition to retirement.

Many self-employed persons have insured their earnings below the legally required level. As a result, their pension accrual is lower than that of employees with similar earnings. For some self-employed, this means that they must continue working for a long time.

Publications:

- Alasoini ym. 2022. Työelämän ja työmarkkinoiden muutos: Haasteita ja kehittämistarpeita sosiaaliturvan uudistamiselle. (Julkaisuarkisto Valto)

- Järnefelt 2016. Working Conditions and Working Lives – Research on the Stability of Working Lives and Retirement (Julkari)

- Nivalainen et al. 2020. How do the self-employed insure themselves? (Julkari)

- Riekhoff et al. 2019. Working-hour trends in the Nordic countries: Convergence or divergence? (Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies)

Light entrepreneurship is a growing phenomenon

Light entrepreneurship is often described as a form of work where the worker uses a billing service company without having to set up their own business. It can be used for platform or gig work, but it is not platform work itself. According to Finnish legislation, light entrepreneurship is not an official labour market status; people are either employees or self-employed persons. Light entrepreneurs are responsible for organising their own pension security.

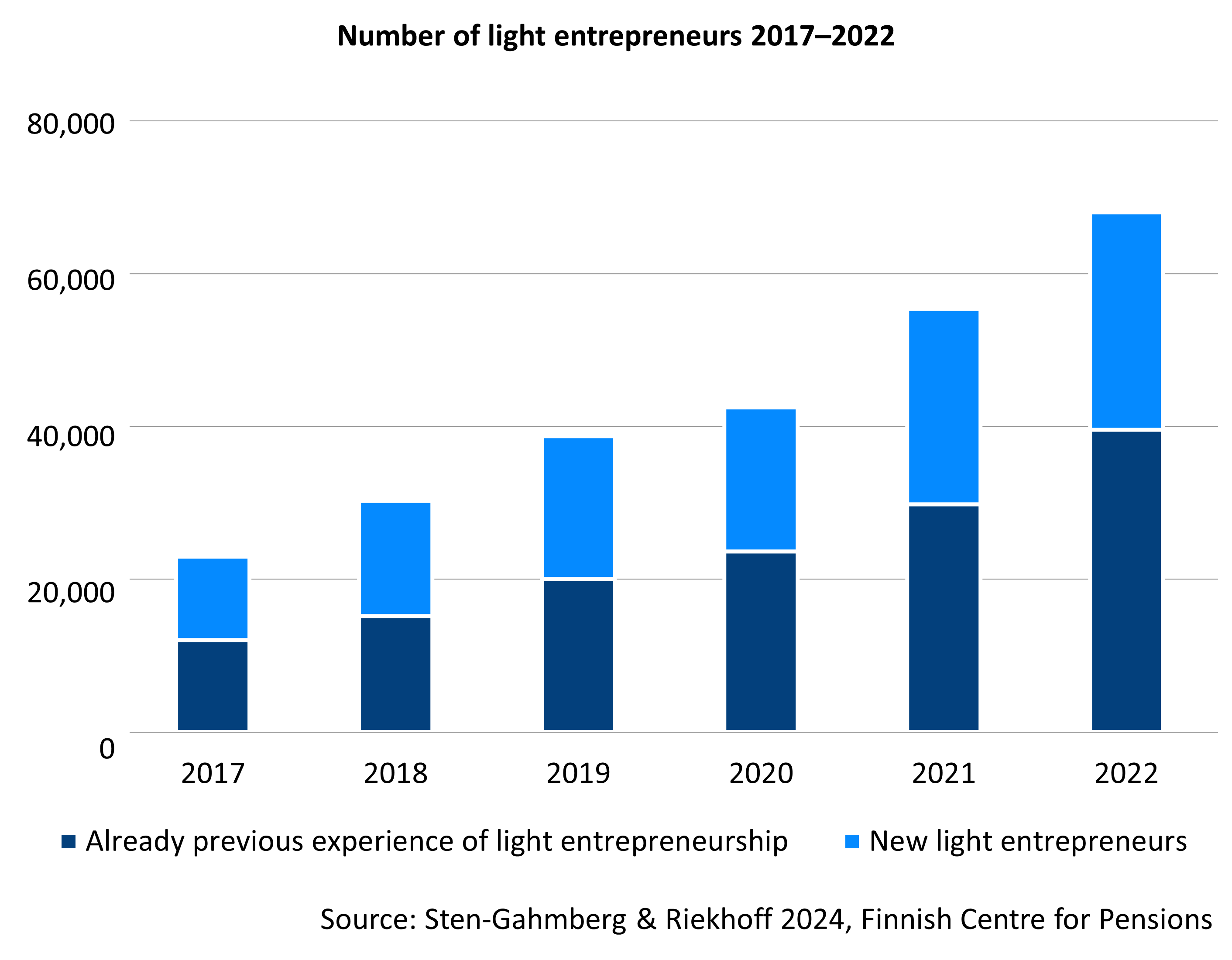

The number of light entrepreneurs has grown rapidly in recent years. In 2017, around 23,000 light entrepreneurs were earning an income through a billing service company, but by 2022 this number had almost tripled to 68,000.

Light entrepreneurs come from different backgrounds and their profile has changed between 2017 and 2022. They are increasingly younger, more likely to have a migrant background and to have only basic education. However, most light entrepreneurs are still men born in Finland, typically aged 20–40.

Light entrepreneurship is often short-lived, with around 40–50 per cent of light entrepreneurs being new each year. In most cases, light entrepreneurship serves as an additional source of income. In 2022, four out of five light entrepreneurs had other income in addition to their light entrepreneur income. Almost 60 per cent of them were also employed.

The median income from light entrepreneurship was 1,700 euros in 2022. In general, employment and income for light entrepreneurs increase after starting up, especially for younger people, those with a migrant background and those with only basic education. However, pension accumulation for light entrepreneurs does not increase significantly or increases only slightly in the years after starting a business.

Graph’s “Number of light entrepreneurs 2017–2022” data in accessible Excel file.

Publications: