Destabilised careers, poorer pensions?

Globalisation, deindustrialisation, automation, digitalisation and liberalisation are often believed to make working life more fragmented and unstable. We investigated such claims in the recently completed project “Fragmented work careers?” (“Pirstoutuvatko työurat?”), led by researchers of Tampere University. Overall, we found no definitive trends towards fragmentation and destabilisation in Finland. However, we identified persisting labour market inequalities between genders and socioeconomic groups. These findings have important implications for pensions as well.

Part of the project focused on trends in career stability across cohorts, using detailed labour market data for almost the entire Finnish working population born between 1958 and 1972 (Riekhoff et al., 2021). We looked at careers between the ages 30 and 44, or so-called “mid-careers”. Between these ages, we recorded individuals’ labour market statuses (e.g. employment, unemployment, in education) at the end of each year. We were also able to identify whether individuals stayed with the same employer and how often job changes took place. An individual’s mid-career stability is measured by a single indicator (the so-called “turbulence index”), which is calculated on the basis of the number of different labour market statuses, job spells and their durations. A value of 1 means the person experienced no changes in the labour market between the ages 30 and 44. The higher the value, the more unstable the career.

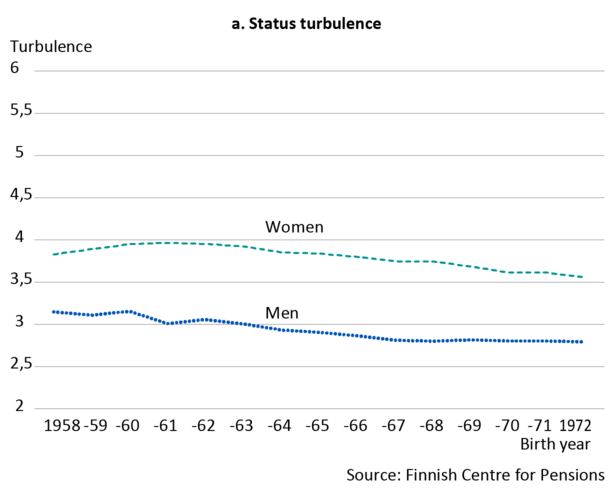

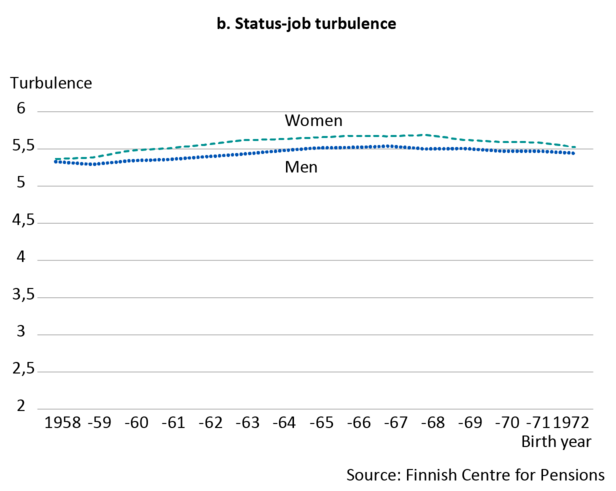

We calculated the average career turbulence for 15 subsequent birth cohorts in two different ways: a first indicator including only transitions between employment and non-employment and the second additionally including transitions between employers. The Figures a and b below summarises the main findings.

Figure a.

Figure a shows that, if only taking into account changes in and out of employment, there is even a slight increase in stability across cohorts. However, women’s careers remain more unstable than those of men. One explanation for this is that women are at least more likely to have career breaks due to having children.

Figure b.

If changes between jobs are included (Figure b), there are no substantial differences between men and women. Career instability including job changes increased somewhat across cohorts, but not drastically.

Career stability matters for pension accrual

Career stability matters from the perspective of the earnings-related pension system. The first dimension of a stable career, continuous (fulltime) employment, is the best guarantee for a good pension (Kuivalainen, Nivalainen, Järnefelt, & Kuitto, 2020). The obvious reason is that in an earnings-related pension system, any breaks from paid work mean no or lower pension accrual.

Still, career interruptions have another impact on pensions. Breaks in working life are associated with lower earnings and less earnings mobility afterwards. It is likely that those with interrupted early- or mid-careers, especially women, will not catch up in lifetime cumulative earnings and that this disadvantage will be reflected in their pension income (Kuitto, Salonen, & Helmdag, 2019).

Regarding a second dimension of career stability, namely employment with the same employer, one might think that changes in jobs do not affect pension accrual, as long as one is employed and earns a salary. However, changes in jobs and job mobility are related to earnings and earnings mobility across the life course, albeit in a variety of ways. Longer tenure with the same employer is usually associated with steady and higher earnings growth. However, if people change jobs voluntarily, they might move to a better job with higher earnings and better possibilities for promotion and development. On the other hand, if the job change is involuntary, for example due to being laid off or because of the need to combine work with care obligations, the job change might be accompanied by lower earnings and lower earnings growth (Fuller, 2008).

No large changes in career stability between cohorts, but inequalities in the labour market persist

Although we did not witness a clear trend towards career destabilisation during recent decades, we did find persisting disparities in career stability by gender, level of education and sector of employment (Riekhoff et al., 2021). These differences will continue to affect inequalities in retirement and pensions. Women in particular have more unstable careers due to changes in and out of employment, which implies lower and slower pension accrual throughout their working lives.

Moreover, we found that the mechanisms behind the career stability indicator that includes job changes were different for men and women. Among men, unstable careers were more common when they were higher educated and when unemployment rates were lower. Among women this was the other way around: their careers were more unstable in the case of lower education and higher unemployment. This finding suggests that for men, unstable careers are a sign of greater job- and, possibly, earnings mobility. For women, an unstable career might indicate involuntary job loss and lower earnings growth.

How to deal with these inequalities? Higher pension accrual rates for time spent outside paid employment might help. Möhring (2018) argued in favour of more distributive basic or targeted pensions to address the gendered impact of career breaks on retirement income. Obviously, gender differences would be smaller if men took more time off for childcare, allowing their spouses to continue to work.

Our findings imply that there is also an explicit need for labour market policies to support equity in pensions through removing barriers to greater earnings mobility. Such policies should support job stability and security for those who need it and promote upward and cross-sectoral job mobility among those who benefit the most from it.

Read more about the Fragmented work careers? project on Tampere University website.

References

- Fuller, S. (2008). Job mobility and wage trajectories for men and women in the United States. American Sociological Review, 73(1), 158-183.

- Kuitto, K., Salonen, J., & Helmdag, J. (2019). Gender inequalities in early career trajectories and parental leaves: Evidence from a Nordic welfare state. Social Sciences, 8(9), 253.

- Kuivalainen, S., Nivalainen, S., Järnefelt, N., & Kuitto, K. (2020). Length of working life and pension income: Empirical evidence on gender and socioeconomic differences from Finland. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 19(1), 126-146.

- Möhring, K. (2018). Is there a motherhood penalty in retirement income in Europe? The role of lifecourse and institutional characteristics. Ageing & Society, 38(12), 2560-2589.

- Riekhoff, A.-J., Ojala, S., & Pyöriä, P. (2021). Career stability in turbulent times: A cross-cohort study of mid-careers in Finland. Acta Sociologica, ahead of print publication.